The fewer opposing arguments, the more plausible the thesis. This seems counterintuitive at first glance. We tend to hoard supportive arguments, assuming the more, the better. Wrong.

Ask CIA analysts. They know some tricks on how to make decisions with a limited amount of information in a high-stress environment. On top of that, if being wrong, there are serious material repercussions. As market participants, we can learn a lot from intelligence analysts.

Any profession requiring collecting, sorting, classifying, and analyzing vast amounts of information shares common characteristics with stock-picking. Accordingly, there are many pitfalls in that process.

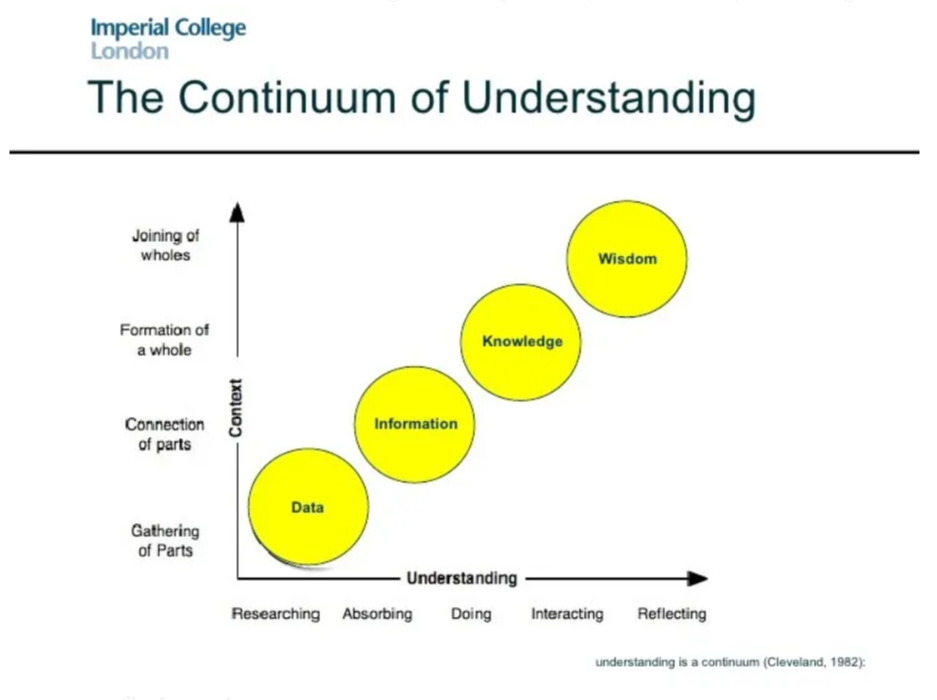

The chart below shows the Continuum of Understanding. Chart via Medium.

At every step, we are tempted to take the path of least resistance. Eventually, we pay for that with an incomplete and poorly argued thesis that leads to inadequate actions and, hence, disappointing consequences.

Our task as investors is to transform the raw data into wisdom in the most efficient way possible. To emphasize, it is not perfect or the best. Such does not exist when we discuss open self-emerging systems with infinite participating agents and dominating nonlinearity.

Yes, I am talking about financial markets. The markets are dominated by known unknowns and unknown unknowns. How to survive and (potentially) thrive in such an environment?

Intelligence analysis is one of the professions from which I draw the most inspiration. These people always work with incomplete information, and their decisions based on the conclusions they reach have material consequences.

In many ways, this is like investing. We always have a tiny fraction of all the information available. At best, we can minimize the information we don't even know we don't know.

What all good intelligence analysts have in common is adherence to a few principles:

Invert. Start from the end and then reason how we arrived there.

Focus on the opposing arguments, not on the supportive arguments.

A balance between data-driven and conceptually driven analytical approach

The list seems too remote for investors. We use technical indicators, macroeconomic metrics, and business fundamentals. However, there is a hierarchy in any analytical process. The bullet points above represent the guiding principles behind our analytical approach, and the indicators, metrics, and fundamentals are our tools.

Treat the principles as a safety manual. It tells us how NOT to use tools and then describes how to use them safely and efficiently. Our job as market participants is to understand the role of each tool. All-round tools do not exist. The instruction manual reminds us of that fact, so we can use every tool only when applicable.

Invert, always invert

Instead of asking how event X can occur, imagine it has already happened. Then our question becomes in the past tense—why did event X happen?

Humans are not wired to think about non-linearity and the future. We are much better at analyzing the past. By flipping the question, we hack our brains, changing the perspective. Instead of ex-ante, we analyze ex-post, so our brains remain in their comfort zone.

In other words, we stop staring at the unknowable future and look at the (hypothetical) past. Thus, our temporal perspective changes from present to future and to present to past.

Explaining why the price of oil will reach $250 a barrel is not easy. Let's try to reverse the question. The difference is only in the tense of the verb "reach." However, it turns our perspective 180 degrees - instead of staring into the impenetrable future, we look to the familiar past.

Looking back, we immediately get ideas of why oil would reach $250/bbl - a partial blockade of the Strait of Hormuz, a sharp OPEC+ output contraction, and full sanctions on oil exports from Iran or Russia. This brings to mind many ideas we would otherwise ignore if we were looking to the future.

Of course, zero-fail rate tools do not exist. The same applies to this one. By reversing the direction of time, we are making assumptions, and our assumptions love to be wrong.

To avoid this trap, we go to the following principle.

Do not seek supportive arguments, instead seek for opposing ones

We have reversed the flow of time and put together several arguments as to why oil will reach $250/bbl. We assume that the more supporting information we have, the more our hypothesis becomes more plausible—a dangerous fallacy.

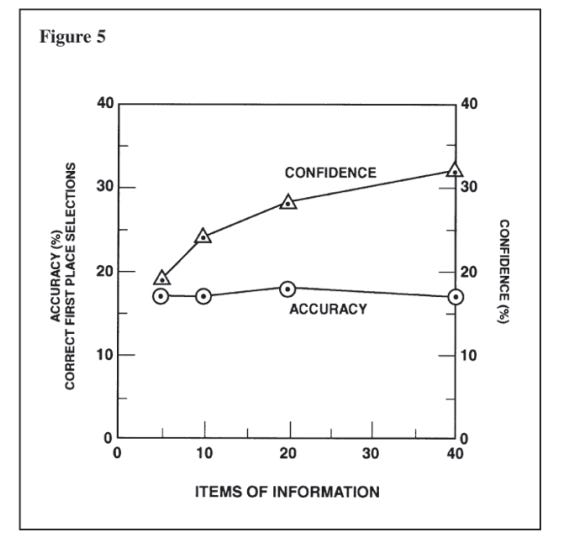

The quantity of information is not directly proportional to the quality of the hypothesis. The only thing that grows in sync is our conviction that we are right. That leads to wrong conclusions and decisions with negative consequences.

We do not seek to gather as much supporting data as possible but rather to find as much data as possible rejecting our idea. The fewer opposing arguments, the more plausible the thesis.

So, our task is to focus on opposing arguments. If a newly assigned value on the existing variable is found and contradicts our original thesis, it's time to dig deeper. On the other hand, if the hierarchy of the arguments shifts and the new structure disputes our view, dig deeper.

I wish to emphasize that quality analysis does not mean a thesis supporting our view. Indeed, it describes the equality of our analytical process. For a prudently designed and meticulously executed analytical process, our views do not matter. The outcome is a well-researched thesis with fewer opposing arguments.

Let’s give an example. I am long PGMs. If you (dis)like mining, platinum, South Africa, or EVs, it does not matter. The material facts matter. In that case, demand and supply.

In addition, the number of objections to my PGM thesis is decreasing. The prime objection was that EVs are present, and ICE cars are an extinct species. Hence, no one needs platinum except rappers. However, the tide has shifted. All large automakers announced that ICE cars will stay with us for longer, so one objection is less.

As a heurist, you can write supporting and opposing arguments in two columns. Like a balance sheet, it shows the present stage of our thesis. It could be overweight on assets (supportive arguments), while the liabilities (counter-arguments) rapidly rise, or the assets are few, while the liabilities are even fewer. Seek a thesis that falls in the former category, lean on assets, yet leaner on liabilities.

This principle is a form of inversion. In the previous chapter, we discussed time inversion (TENET is one of my favorites, so a piece on Nolan and investing is coming soon). In that section, I present logic inversion, focusing on negation instead of affirmation.

Left hemisphere vs. right hemisphere

There are two formal analytical approaches: data-driven and conceptually driven. Analysis based on data processing is more subordinate to the left hemisphere, while that of concepts is to the right.

In recent decades, science has dominated. It has become the new religion, focused on the material world and the idea that everything is subject to logical models. This is partially true.

The world is not black and white. Linear thinking is an excellent tool for specific tasks but fails in many others. By focusing on logic, we ignore creative thinking, pattern recognition skills, or simply perceiving the flow.

If we want to progress as a civilization and as individuals, we must master both hemispheres: logical thinking in processes and intuitive perception of flow. If we decline to do so, we end up like the man who wants to run fast using only one leg, assuming the second is useless.

How does all this relate to analytics?

A qualitative analytical process requires synchrony between the left and right hemispheres. Each half of our brain performs tasks that the other cannot. The left is linear and concentrated, while the right is nonlinear and multidimensional.

As analysts, we must perform qualitatively and quantitatively different tasks simultaneously:

We must see the tree and the forest concomitantly.

We must connect the past with the present and the present with the future.

We must act tactically but think strategically.

We can easily fall victim to one of the hemispheres, discounting the left at the expense of the right and vice versa. Thus, the outcome is an incomplete thesis. Yet our conviction grows disproportionately due to our overreliance on only the hemisphere. Logical reasoning and flow perception must work in unison. Then, the result is a comprehensive analysis considering the macro picture and the tiny details.

Final thoughts

Thinking about thinking. We investors must reflect on that sentence. We are overtly focused on stock picking to figure out the next hot idea, assuming that a positive outcome is guaranteed.

The investing process is simple: research, valuation, and execution. Yet, we fail at every step. Even in the most overrated stage, stock picking, we crash. Today’s article aims to bring a fresh perspective to one of the most prized aspects of investing: the analytical process.

Most investors, even institutional ones, have the wrong mindset. They think investing should be considered a subject of economics and finance—an expensive fallacy. Philosophy, psychology, and history are excluded from the curriculum. In Corporate Finance class, they do not teach thinking about thinking.

The same is true for books on investing and trading. Most of them must be blog posts. That being said, I stopped reading books on trading and investing a long time ago. 95% of them reiterate that we should focus on stock picking and be like Buffet. A sugar-coated partial truths to hook the audience’s attention.

I seek inspiration elsewhere. Professions with high stakes, incomplete information, and betting on future events are promising starting points. CIA analysts and poker players are my role models. The former teaches us how to think about thinking, while the latter teaches us about risk and uncertainty.

It is easier to think of the past instead of the future. Invert the time perspective. The fewer opposing arguments, the more plausible the thesis. Seek more rejecting arguments instead of supporting ones. Logical reasoning and flow perception must work in unison. The result is a comprehensive analysis that considers the macro picture and the tiny details.