War, pandemic, a shaken economy—the world’s end is coming. History despises order and tranquility, unlike people. Disorder and constant change are standard, not an exception, from a historical point of view. Despite that, we would like to forget it. We cannot comprehend the big picture, remaining blind to the macro processes.

History follows generations-long cycles. Of course, these cycles are imprecise and sometimes deviate within a decade. But from a historical perspective, ten years is the blink of an eye.

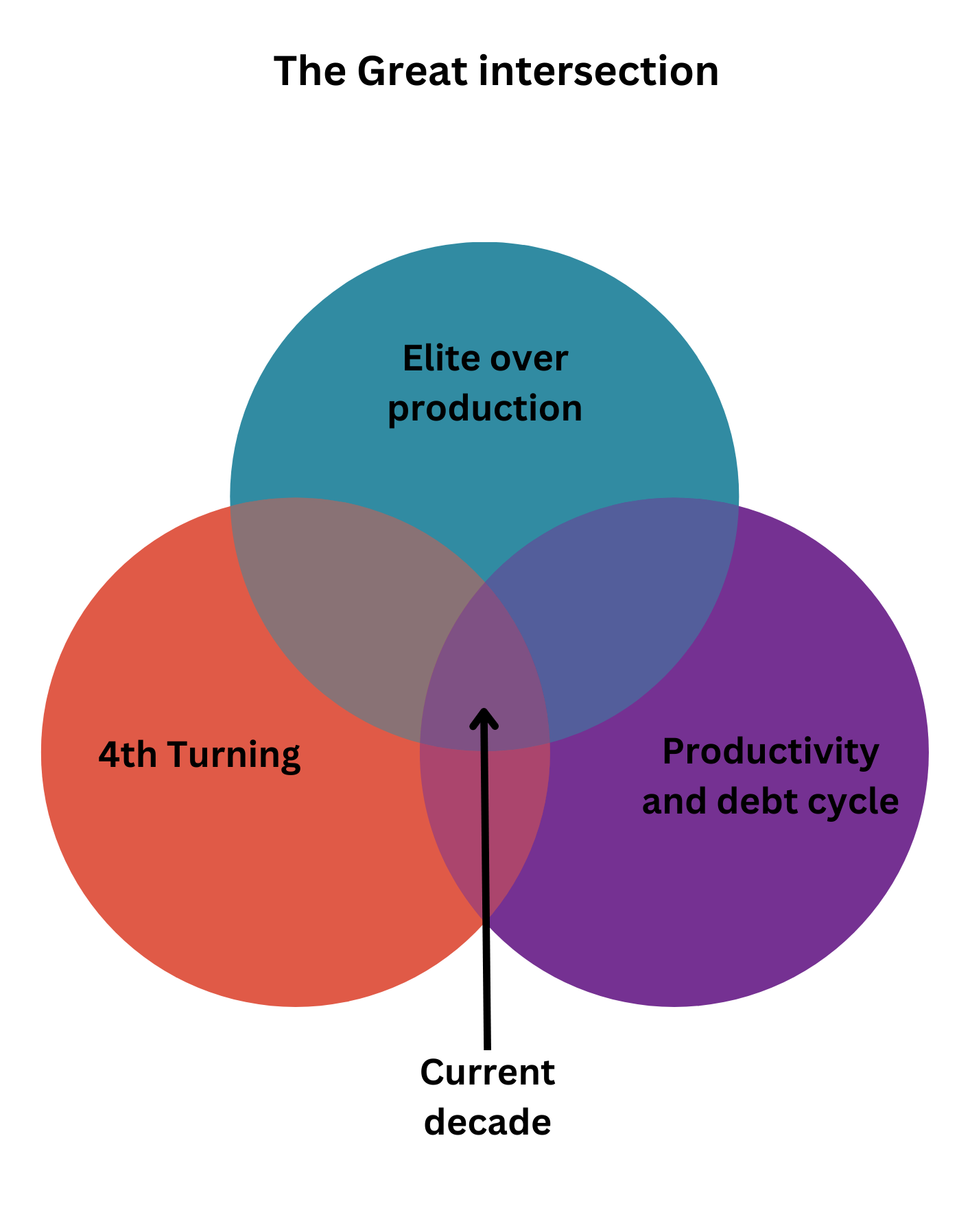

In the present decade, the inflection points of more than a few cycles coincide:

Generational theory and 4th turning - Strauss and Howe

Elite overproduction cycle - Peter Turchin

Productivity growth and debt cycle - Ray Dalio

The synergy between the cycles will initiate another paradigm shift. The changes will profoundly shape our future in every aspect. I discuss how those cycles will impact the coming years in today's article. I promise it will be a turbulent yet rewarding trip.

Generational Theory and the Fourth Turning

Strauss and Howe reached curious conclusions by studying the history of North America and Europe. They find that every 80-100 years, a new cycle begins in society. Each cycle describes the dominant paradigm of the era. Each one is divided into four parts, lasting 20-25 years. Those sub-cycles are called Turnings, characterizing the stage of development of society:

First Turning—The High is a recovery period after the previous crisis. It is characterized by a strong state and weak individualism. Collective goals are more important than individual goals, and idealism and high morality are dominant values. The generation that successfully brought the country out of the crisis holds power. It sets the rules of the game—political, economic, and cultural. In the United States, this is the period immediately after World War II until the early 1960s.

The second turning—The awakening is a period of asserting individual identity. The children of the generation that went through the crisis enter adulthood. They rebel against the norms imposed by their parents and the domination of the collective over individual values. The generation that survived the last turbulent period still holds the levers of power. Despite increasing individualism, the state is still strong. This is the period from the early 1960s to the mid-1980s in the United States.

Third Turning - The Unraveling - after the affirmation of individualism, the period of "eternal" prosperity begins. The state gradually weakens at the expense of the individual. The generations that successfully went through the last crisis more than 50 years ago are retired and have no real power. Their children have not experienced profound crises. They believe life equals guaranteed prosperity with minimal shocks. All the levers of power are in this generation - baby boomers in the United States. Comfort and security become the main priorities. These are the dominant values of society. In the United States, it runs from the mid-1980s to the beginning of the 2008 crisis.

Fourth Turning - The Crisis - a period of turbulence in society. The generations directing the macro processes have yet to experience dealing with crises. A lack of values and extreme polarization in every aspect characterizes this period. Priorities go beyond comfort and security; the new values are consumption and pleasures at all costs. Society is increasingly divided into factions because no shared goals, such as humanity and prosperity, exist. This period has always been filled with cataclysms - wars, revolutions, and recessions. The beginning of this period is 2008, and it ends in this decade.

The spirit of the times and the people’s character in each turning corresponds to each stanza of the following poem.

Strong men create good times,

Good times create weak men,

Weak men create difficult times,

Difficult times create strong men.

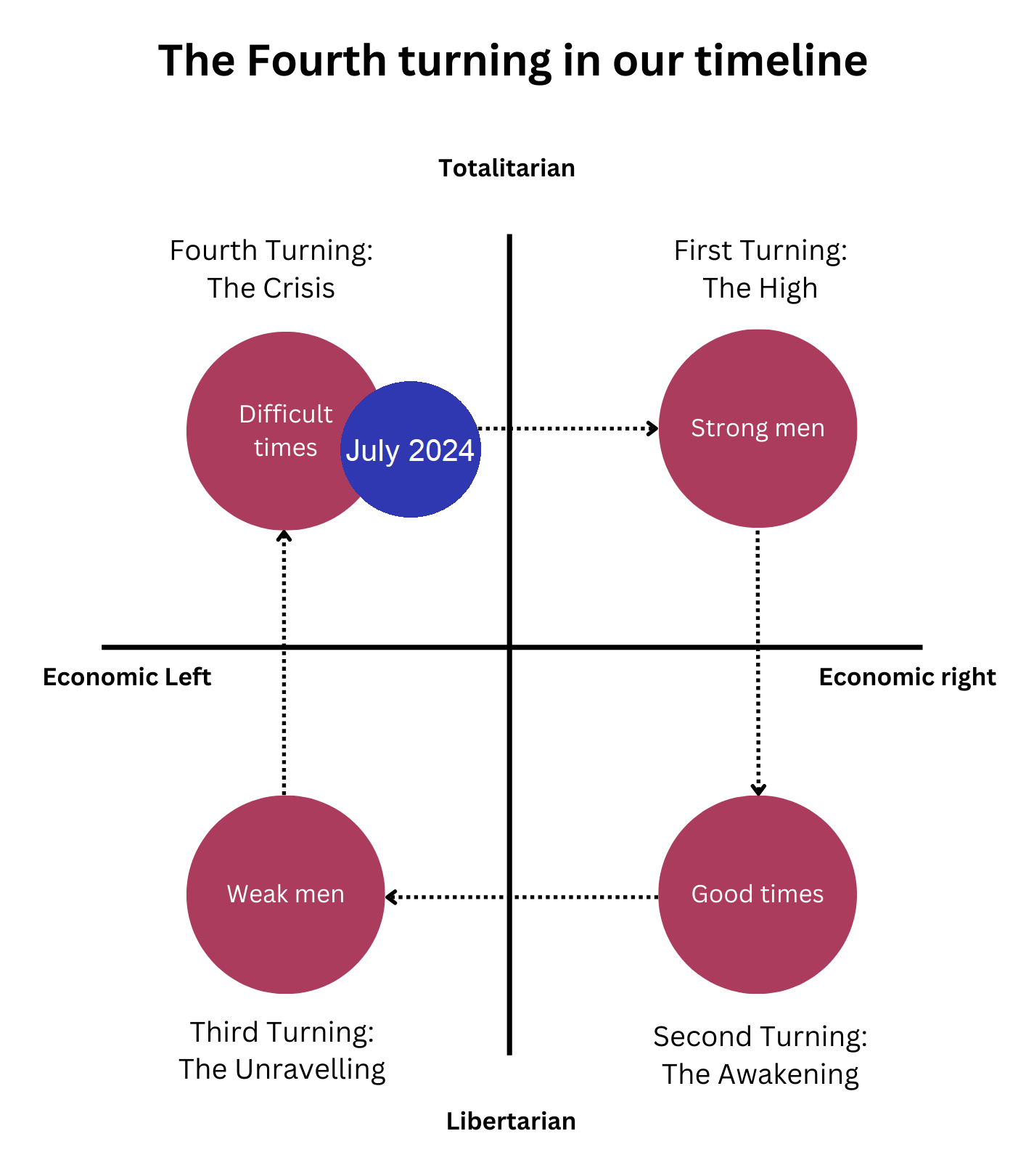

All the above can be compressed into the following graph:

We are currently in the middle of the last stage. The surrounding world constantly reminds us of this - from replacing values under the banner of social justice and cultural Marxism through inadequate political and economic decisions in developed countries to the quality of contemporary art (films, music, fashion).

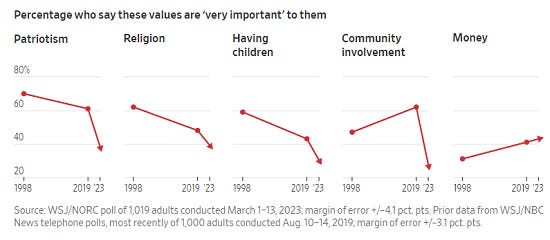

The graph below shows the sustainable trend of the degradation of values.

Until recently, values considered immutable and undisputed are losing their attractiveness. They give way to a way of life that follows the YOLO and FOMO principles. With this way of life, everything must happen now - the past and the future do not exist. We are devoured by the eternal now.

Every century has its 4th turning, and I don't see a reason for ours to be an exception. Yes, it may happen the next year or in 10 years, but it will happen. It doesn't have to be a major military conflict, but we will likely go through one.

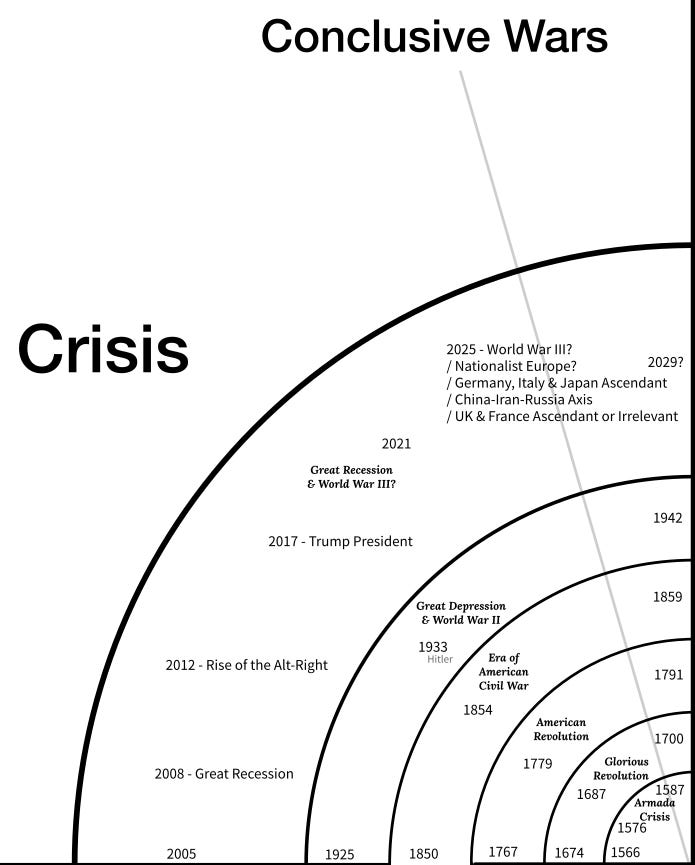

The following chart provides historical context:

We can see how these cycles unfolded and corresponded with historically significant events in the past, from the clash between the Spanish Crown and England through the American Civil War and WW2 to the present day.

Generational theory describes the development of societies in North America and Western Europe. At first glance, it seems there is nothing to do with the rest of the world. However, even if that is the case, it doesn't matter because Western civilization still dominates the world, holding all levers of power - economic, military, political, and cultural.

Any radical change in the Western world affects all others. The state of the core predetermines the state of the periphery.

Conclusion: The current generation leading the developed countries has yet to experience deep crises. No statesmen like De Gaulle, Eisenhower, or Thatcher have long existed. Current politicians worsen the situation by making foolish decisions to fix essential but not-so-striking problems. Every easy-to-solve problem can become severe if we approach it wrong. We are in the middle of the last stage, meaning the most interesting is yet to come.

Elites’ overpopulation

Peter Turchin is a pioneer of the discipline of cliodynamics. It is the intersection of history, economics, and sociology. It uses mathematics tools to describe social and civilizational macrocycles. Peter's two fundamental theories are the structural-demographic and elite overproduction theories.

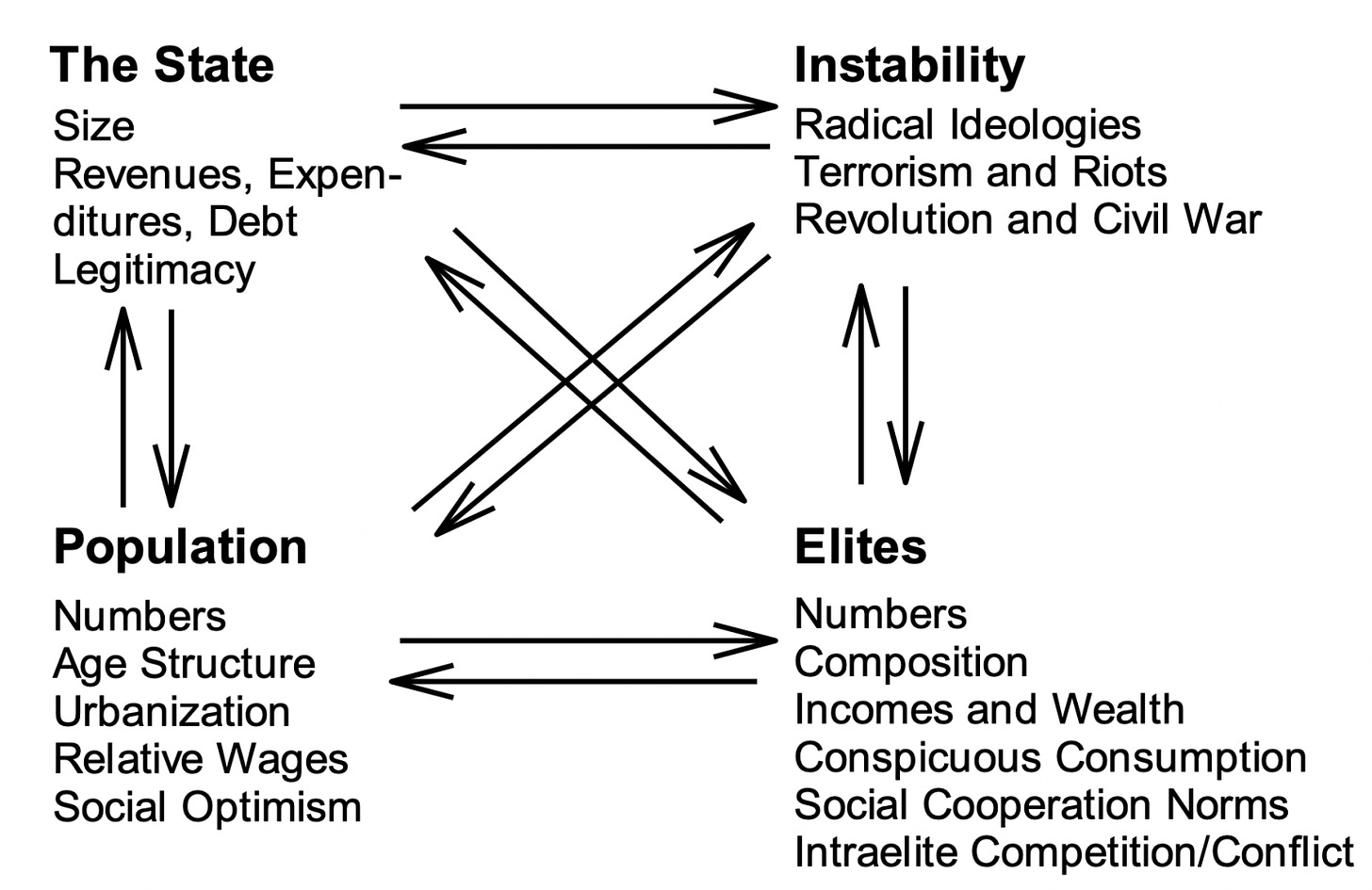

Structural Demographic Theory (SDT) analyzes and predicts political instability in modern societies. Society is a system of three elements plus one more: population, elites, state, and sources of instability.

The three groups shape every society; the fourth element is the catalyst, i.e., the spark that triggers the other three and leads to changes in the social order. The following image shows their relationships:

As seen, the relationships are two-way. Each element is a cause and a consequence and interacts with all the others. According to the stage of development of society, the valence and intensity of the relationships vary. They carry informational value as to how the future could develop based on an analysis of the past.

Elite Overproduction Theory (EOT) stems from the previous theory and examines in detail one of the three social groups - the elites.

By elites, the author means a group of society that holds legally guaranteed social power in their hands. The commonality among all members of the elite is that they are highly educated, have high income, and through their activities, they have power over groups of people.

The theory argues that the more people belong to the elites, the more inequality grows. The elite concentrates overwhelming power and capital at the expense of others. However, since both are finite resources, this exacerbates inequality in society.

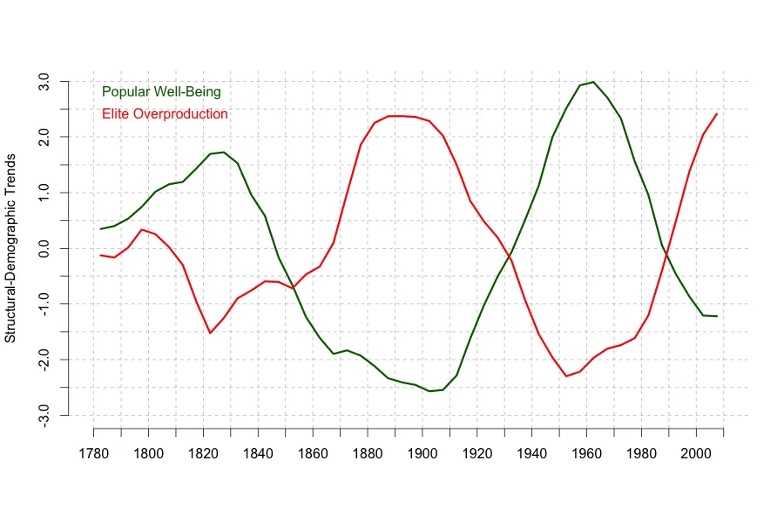

Inequality leads to dissatisfaction, which, if it reaches a boiling point, leads to political unrest. The following graph shows the correlation between the described variables:

The correlation is apparent—the relationship between the population's average life satisfaction value and the increase in the number of the elite is inversely proportional.

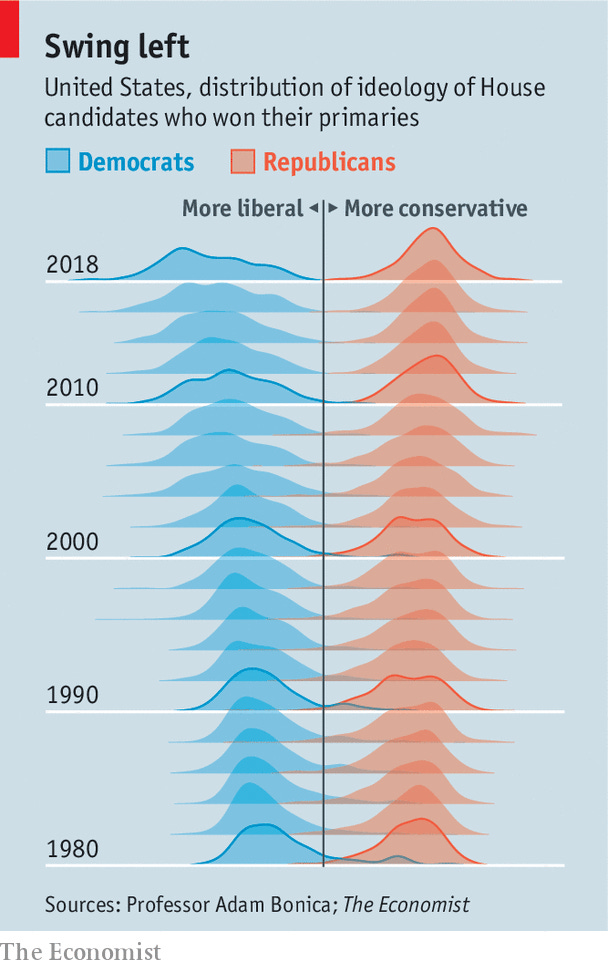

The increasing division in society is a consequence of the first order. More extreme opinions begin to dominate. Politicians on both sides of the spectrum rely on increasingly polarizing campaigns. Over the past 40 years, this has been a slow but sustained trend.

Political polarization is a result of pronounced inequality and dissatisfaction of the majority. As can be seen, Republicans and Democrats are becoming more extreme in their opinions. This leads to a need for more dialogue between the two groups, which further exacerbates the division.

Conclusion: Concentrating capital and power in smaller groups of people will continue, leading to a more polarized society and predisposing it to political instability.

Productivity and debt cycle

The economy follows liquidity, not vice versa. The most crucial financial equation looks deceptively simple:

Money = credit + cash

The first variable on the right side is significantly more important than the second for one reason - money created as credit accounts for over 90% of all money in circulation. In other words, a considerable portion of the demand for goods and services directly depends on creating money through credit.

In a cash transaction, we receive a good or service and pay immediately, whereas in a credit transaction, we promise to pay later. This transaction is complete once the borrower fully repays the credit. That process creates money out of thin air as long as two parties agree to the transaction terms.

Central banks do not create credit (money); they only set the price of its creation - the interest rates. The lower the interest rates, the cheaper the money, and vice versa. In the first case, more credit is drawn (more money is created); in the second, less credit is drawn (less money is created).

The ability to create money through credit is cyclical. The amount of money in circulation directly impacts the economic machine. As a result, three fundamental forces dominate the economy: productivity growth, short-term debt cycle, and long-term debt cycle.

Productivity Growth

The average GDP growth rate has been 2% yearly for centuries. It is dictated by the accumulation of knowledge that directly affects production methods and efficiency. New knowledge becomes new technologies that fix previously unsolvable problems. Thus, the standard of living steadily increases. Over the last 50 years, we have lived unprecedentedly comfortable lives.

Imagine how the wealthiest person in the world at the time, John Rockefeller, lived 100 years ago. He had a splendid mansion in Manhattan, an incredible art collection, and money ten generations couldn't spend.

However, nowadays, the average person in Europe, North America, and parts of Asia has access to fast and cheap transportation to any point on the globe, instant communication with anyone 24/7, and highly specialized medical care. All these did not exist in Rockefeller's time. No matter how much money he had, he could not buy something yet invented.

But we humans are curious creatures who are unsatisfied with what we have. We always strive for more and often surpass our abilities to get the object of our desires. The gap between what we want and can is filled with credit.

Credits are like drugs, stimulating the brain’s pleasure centers and releasing large amounts of dopamine. Dopamine makes us live in the moment, staying in the eternal present. We follow the mantra: spend now, think later.

In the long run, we can only spend as much as productivity growth rate. Productivity growth averages 2% per year, which limits the amount of credit the system can take on.

For short periods, the amount of credit grows faster than productivity. This stimulates demand, which further increases productivity until the servicing of the obligations becomes unbearable. Then, demand contracts and productivity shrinks. This cycle of leveraging and deleveraging creates short-term and long-term debt cycles.

Short-term debt cycle

The business cycle typically lasts 5-7 years and is directly dependent on the policies of central banks. Their task is to regulate growth, inflation, and unemployment through the three levers at their disposal:

Changes in interest rates

Open market operations

Banks reserve requirements

The three levers determine liquidity, the amount of credit (money) circulating in the system. Demand directly depends on the money created.

Record-low interest rates have dominated the last decade. A tremendous amount of money was created through credit, stimulating demand for all sorts of assets and leading to inflation.

When the prices of all assets increase, the net wealth of their owners, at least on paper, grows. Low interest rates motivate people to take even more loans, using their appreciating assets as collateral. This creates even more money through credit, and the prices of everything continue to rise.

Inflation eventually gets out of control, and interest rates must be raised to tame demand inflation. It depends directly on the new credit created; higher interest rates reduce the money made through credit. Thus, demand will be suppressed, and inflation will cool down.

Reducing inflation by creating more supply (goods and services) takes much longer – a new copper mine takes at least ten years to develop, and a chip factory takes at least five.

However, interest rates are raised until the prices of assets don't fall too much. High-interest rates make servicing debt increasingly costlier, sharply increasing the discount factor, thus lowering company valuations. This leads to even less borrowing, which further shrinks demand.

A new cycle follows, leading to lower interest rates than the previous cycle. And so, we reached the zero-interest rate policy (ZIRP), which has dominated in recent years. This means we've arrived at the inflection point of the cycle, as nominal interest rates cannot become negative. This leads us to the beginning of the end of the long-term debt cycle, which consists of multiple short-term debt cycles.

Long-term debt cycle

These cycles are not widely known because they continue for decades, and long-term thinking is not inherent to humans. They last 25-50 years. This cyclicity has been known since ancient times—in different historical periods, forgiving debts every 50 years was widespread. This is the so-called jubilee.

Short-term debt cycles form long-term ones. Every 5-10 short cycles encompass one long cycle, and the last short one marks the moment of maximum indebtedness and zero nominal interest rates.

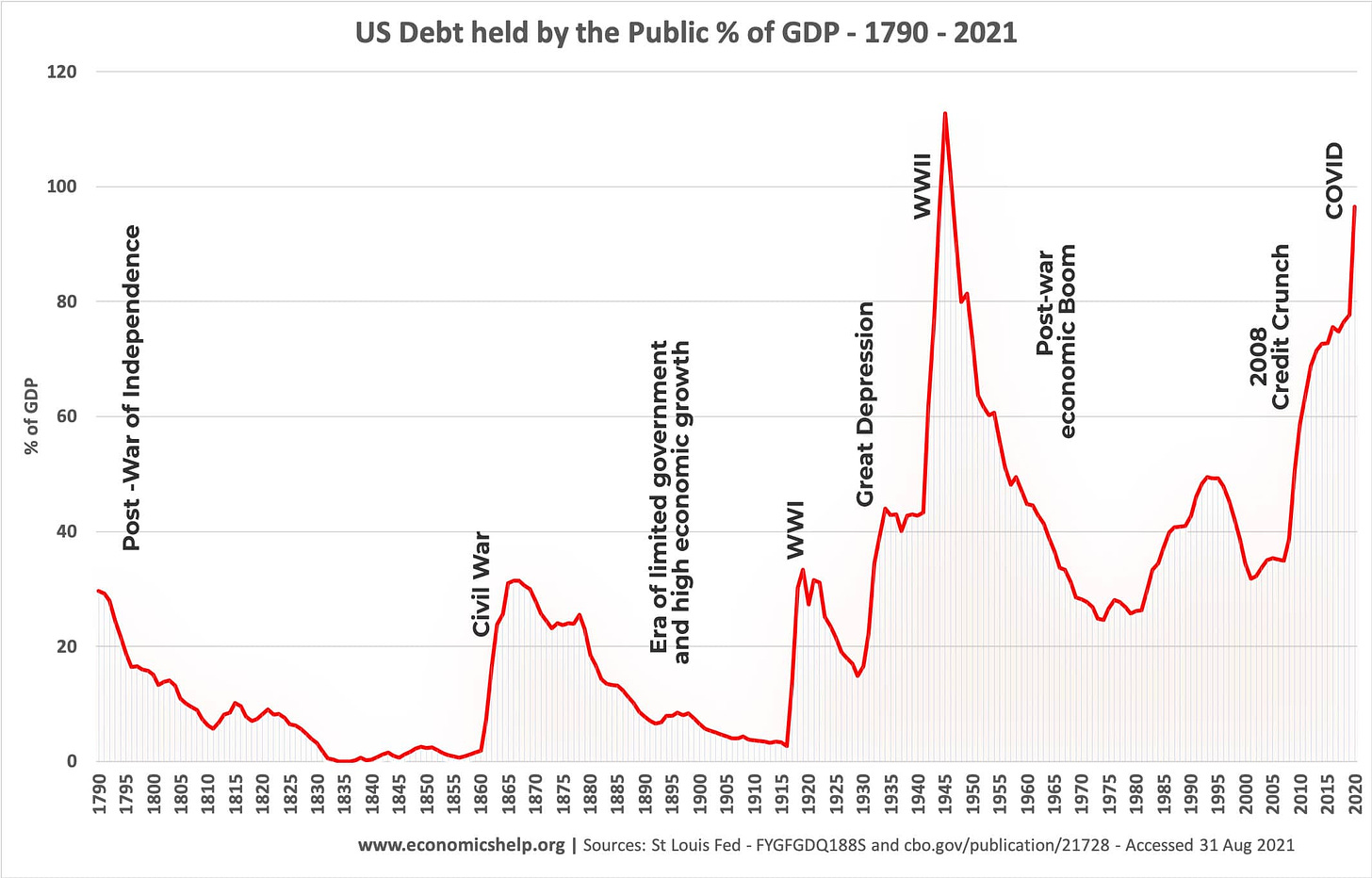

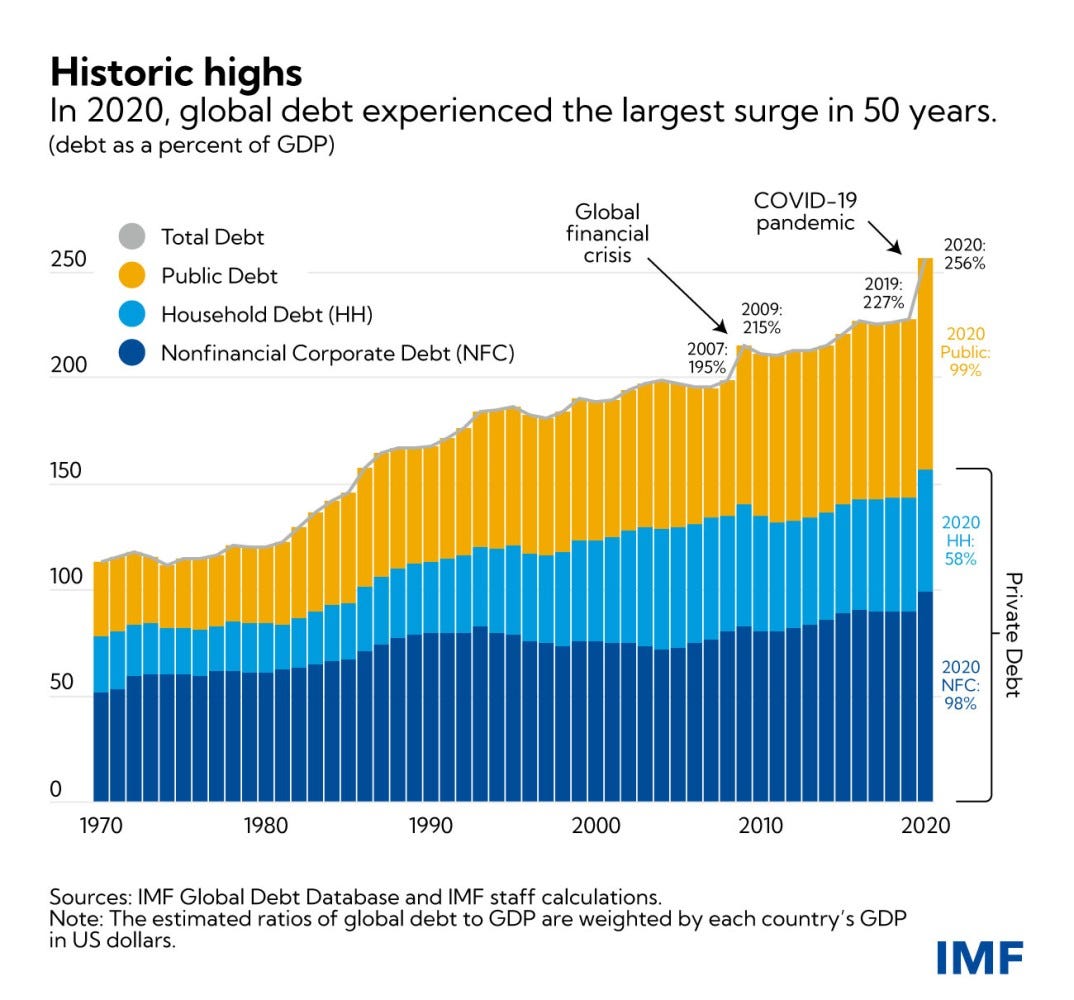

The debt-to-GDP ratio is a very indicative measure, comparing how much we owe compared to the economy’s productivity. I will present you with three graphs. The first shows the debt-to-GDP ratio for the US, the second for the world, and the last shows debts as an absolute value.

The most important conclusion is that the moment to pay the bill will come sooner or later. Nothing in nature moves in only one direction.

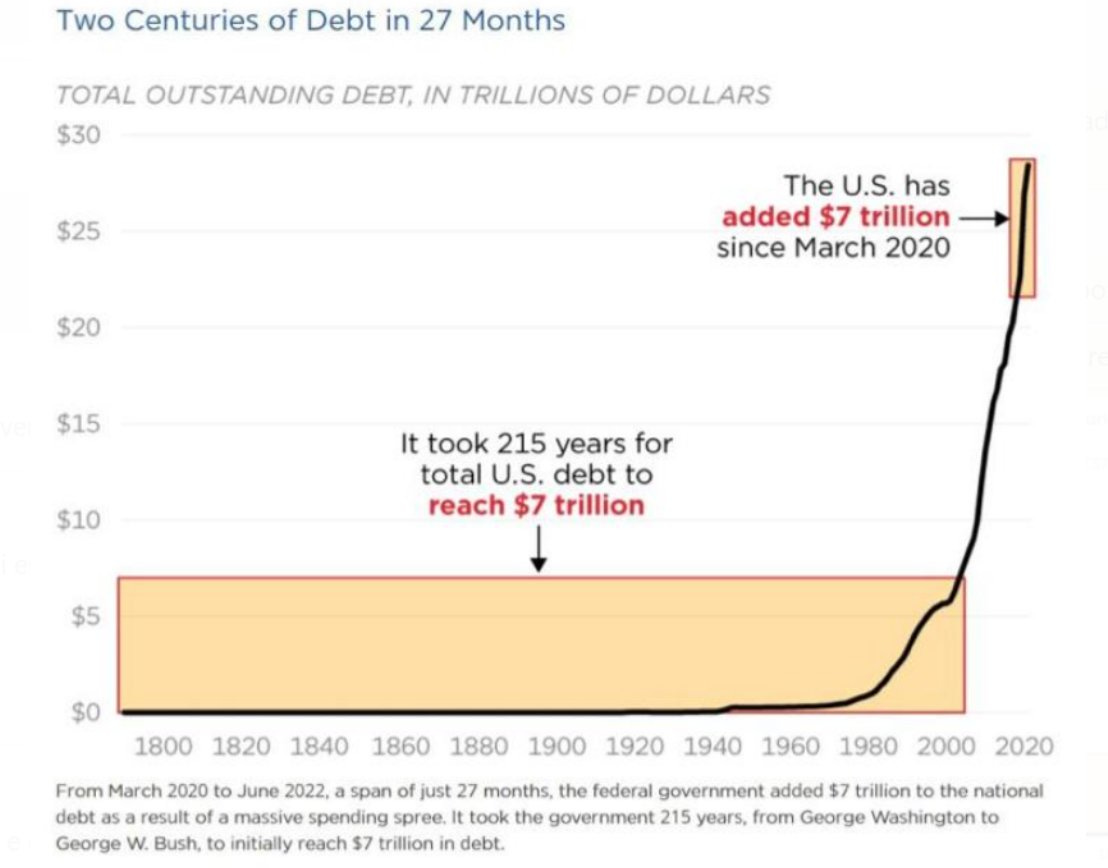

Globally, debt is steadily increasing. The top graph shows the three components of debt and its total value, and the data is up to and including 2020. The peak reached 256% debt to GDP, which means that for every dollar of production, there is $2.56 of debt. The third graph illustrates in absolute value how much we are indebted:

In a complex system with a (in)finite number of variables, the instantaneous doubling of one of the critical parameters inevitably leads to drastic changes in the entire system’s state. In the last four years, as much debt has been created as in the previous 215 years.

The questions are twofold: when will the bill come due, and how big will it be?

"No tree, it is said, can grow to heaven unless its roots reach down to hell."

Carl Jung

The development of technology stimulates productivity, which grows at an average of 2% per year in the long term. However, civilization needs fuel to produce and spread these technologies. And that fuel is money.

Money consists of cash and credit. The second component is more important, representing 90% of the money supply. Creating money through credit follows short cycles that are part of long cycles.

Conclusion: in the short term, the debt growth rate may exceed the productivity growth rate, but in the long term, debt always returns to values corresponding to current productivity.

We have entered the peak period of another long debt cycle. In the coming years, we will experience the downward side of the cycle—a contraction of debt—in one way or another.

The inflection points of the 4th turning, the elite overproduction theory, and the productivity and debt cycles coincide with this decade, causing a profound global impact. Changes are inevitable. However, we do not know their polarity and magnitude.

Where are we today?

Increasing degradation and polarization of society, a growing number of incompetent elites, and growing debt relative to productivity. What can go wrong?

All you have read are the author's thoughts, which are limited, biased, and incomplete. What has been written has high informational value, but only time will tell how much it carries predictive value.

The publication is not a pessimistic forecast but a review of the past and present. I expect global changes. They are inevitable, as they have always been. Remember, uncertainty and change are only two guaranteed things in life.

Embrace the changes and the unknown.