How to play AI and green energy?

The magic acronyms: FPSO, FSRU, and FLNG

Take the opportunity to peek behind the curtain of TheOldEconomy paid membership.

Welcome to the Test Drive section. It answers the following question: What will you miss if you do not become a paid subscriber?

It is time to introduce Seatrium Limited, one of the major builders of floating energy assets. The article was published for TheOldEconomy Paid Member in August 2024.

I am long AI and green energy. You wonder how. Basically, by investing in energy. Datacenters make the AI revolution possible. They consume enormous amounts of energy. On the other hand, we have an energy transition. Therefore, we need energy-dense fuel combined with minimum emissions. Uranium and LNG are the answer.

The diagram above tells us everything we need to know. The present level of technology limits us to LNG and uranium. Which does grow faster, uranium and LNG supply or data center energy demand and cleaner energy needs? Given the acute supply destruction typical for the commodity and energy complex, I bet the data centers and cleaner energy.

The supply side is constrained by widely known facts such as a lack of personnel, almost zero CAPEX, and declining ore grades (for metals). On the other hand, energy demand here is poised to grow further. Adding to the mix of Global South demographics, monetary and fiscal exuberance, and geopolitical disorder, we have a recipe for a decade dominated by energy.

This is not my first energy report. In 2024, I covered offshore supply vessels, product tankers, and floating LNG units. The topic of the August report is energy, but from an unexpected angle. Again, the context is floating steal. However, the industry in question is not shipping but shipyards.

Specifically, shipyards focused on building floating energy assets like FPSO (Floating Production Storage and Offloading Vessel), FSRU (Floating Storage Regasification Unit), FLNG, oil rigs, and drill ships. Those heavy pieces of equipment are true engineering wonders. They make deepwater oil field exploitation economically viable. Floating energy assets costs reach a few billion dollars for Floating LNG units. That being said, the technical complexities of designing, building, operating, and maintaining put a massive moat around the few companies able to build such units.

I believe floating energy assets have huge potential to deliver Alpha. Today, I answer how to play bet on that theme. As usual, I start with the big picture, analyzing supply and demand. In that case, it is a shipyard landscape and a market for floating energy assets. Let’s start with the supply side.

Shipbuilding overview

Let’s start with an overview of the industry. The following text summarizes my article on shipyards.

Building a vessel takes 12-36 months, depending on size and complexity. Building a shipyard can take longer. Conversely, vessel demand is erratic depending on fluid variables like day rates and second-hand vessel prices. Simply put, shipyard supply is slower compared to vessel supply.

Every asset-heavy business depends on three variables: labor, material, and capital cost. Shipyards are no different. Those three metrics also define supply and demand. Shipowners also consider the cost of labor, materials, and capital when deciding whether to purchase or not purchase a vessel. This is the general explanation.

Like shipping, shipbuilding is characterized by heavy short-term demand fluctuations and high supply inertia. However, shipbuilding supply is even more inelastic than shipping's.

Over the last fifteen years, all capital-intensive businesses have suffered from supply sanctions. The reason is the well-known lack of CAPEX due to cycle contraction. I believe we are at the bottom of the cycle for energy, mining, and shipping (in broad categories). The same applies to shipyards.

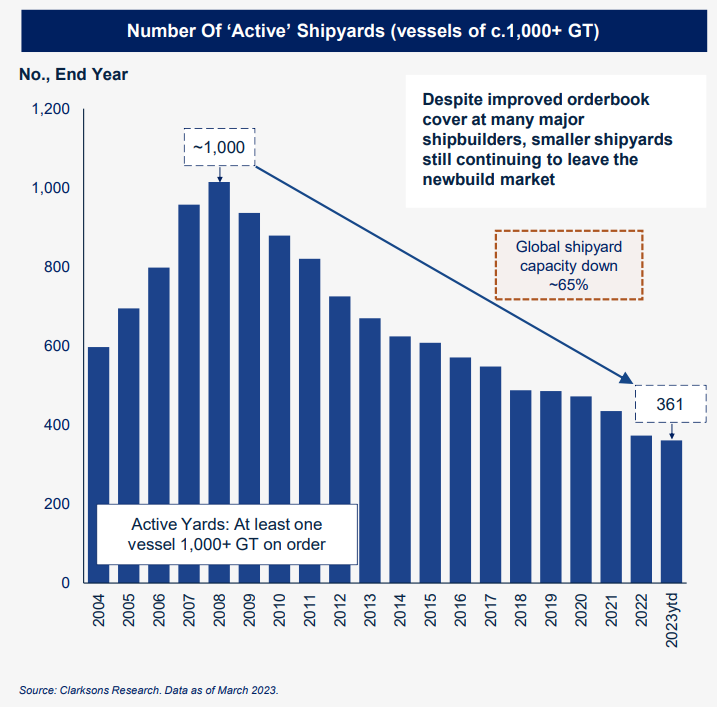

Since 2008, the capacity declined by 65%. Chart via Tidewater.

On the other hand, the queue for new vessels is getting longer, led by LNG/LPG carriers, container ships, and car carriers. Those three segments have double-digit order books exceeding 20%. Crude/product tankers, offshore supply, and dry bulk carriers are catching up, too. Those segments come with low teens or even single-digit order books.

Let’s look at each side of the equation in detail. The supply for shipbuilding capacity depends on the following:

Cost of capital

Cost of materials

Cost of labor

Exchange rates

Subsides

All combined, determine the unit cost and the number of available berths.

Unit cost (the price of a ship) is a function of the cost of the inputs (labor, capital, materials). As pointed out earlier, new vessel prices are volatile, so shipyards may reach a point when they are losing money on vessel builds. Here comes the role of subsidies. They aim to absorb the negative difference between the vessel price and unit cost.

Exchange rates play a huge role, too. All three countries, Japan, China, and South Korea, have different economic policies regarding their currencies. Nevertheless, the role of domestic currency strength compared to the US dollar is indisputable.

Another aspect of shipbuilding supply is the supply chain. Since 2020, we have started to realize how important and fragile they are. Iron ore from Brazil and Wartsila, Finland, has to travel a long way to reach the Far East. The status of supply chains is the first derivative of geopolitical entropy. As a result, I expect more unexpected disruptions caused by growing global tensions.

The cost of labor deserves special mention. I started the article with demography. The population pyramids of China, Japan, and South Korea are no more pyramids. The declining workforce and the growing number of dependents undermine all labor-intensive businesses.

Moreover, mining, shipping, and energy are not attractive to the youth. China is an expectation. It takes years to develop a skilled labor force. Besides that, managerial positions require extensive technical and leadership skills. A rare combination that takes decades to nurture. The subsidies can offset the losses by reducing the costs, but they cannot create new naval architects, engineers, mechanics, and fitters overnight.

The demand depends on:

Freight rates

Second-Hand vessel prices

Market sentiment

Access to financing

There is a simple heuristic about the relationship between freight rates and new-build demand: The higher the day rates, the more ship orders. During the expansion phase of the shipping cycle, shipowners go on a shopping spree for new vessels. However, the delivery usually takes more than 24 months.

So, if shipowners want more ships now to capitalize on rising rates, they must venture into the second-hand market. With increasing day rates, the appeal of the second had ships grows. An old vessel delivered today may cost more than a new ship delivered in two years during a market peak. Vessels of scrap age (above 20 years) are kept in operation, too, as long as the day rates are strong.

And here is the tricky part. The shipowners must reflect on the future. They may order new ships if they expect stronger rates in years to come. On the other hand, the shipowners are not confident in the long term, yet they still expect robust rates in the short term, so a second vessel is a plausible solution. The dominating narrative among the shipping companies creates expectations. Accordingly, the shipowners do not play only market fundamentals but expectations, too.

Access to financing is the last variable that determines the shipyard's capacity demand. This variable has two aspects: the cost of capital and banks' tendency to finance ship purchases. The cost of capital depends on interest rates, and banks’ tendency to fund shipping companies depends on interest rates, shipping market expectations, and shipping market fundamentals.

To recap, I believe we are in the first inning of the shipyard Supercycle. That being said, not all shipyards are equal. Some offer better risk rewards than others. Today, we have such a case: shipyards building floating energy assets.

China dominates the shipbuilding landscape in quantity, yet South Korea still leads when it comes to quality. If we talk about FPSO, FSRU, and FLNG Singapore, it also comes with an attractive offer.

In summary, four shipyards are responsible for over 80% of energy floating asset production: Hanhwa Ocean, Hyundai Heavy Industries, Samsung Heavy Industries, and Seatrium. The first three are South Korean enterprises, while the last is Singaporean. It’s worth mentioning that China is catching up. Chinese yards can build mass-produced vessels such as bulkers and tankers. In recent years, they also started to build LNG carriers, FPSOs, FLNGs, and drillships. Nevertheless, the Chinese yards still lag behind the big four.

The supply side is explicitly limited because only a few yards can build such assets. On the other hand, the demand is not expected to slow down. Deepwater projects are the new old trend in energy. Fueled by green energy, rising energy demand, and growing global chaos, energy majors are focused on developing such projects. That being said, let’s look at the demand side.

The following section is divided into three segments discussing the major floating energy assets: FPSO, FSRU, and FLNG.

FPSO

Over the past ten years, the Atlantic has been the preferred destination for deepwater projects. The leading locations are Brazil, Guyana, Argentina, Namibia, Angola, Senegal, and Mauritania. Petrobras, BP, ENI, Shell, and Exxon are investing billions in developing deepwater oil fields.

Special equipment is needed to extract, store, and offload offshore crude oil. FPSOs are built with this purpose in mind. Almost 40 years ago, Shell commissioned the first facility dispatched to the Shell Castilian oil field in the Mediterranean. Since then, the reliability of FPSOs has been proven, and they have become an integral part of fossil fuel production.

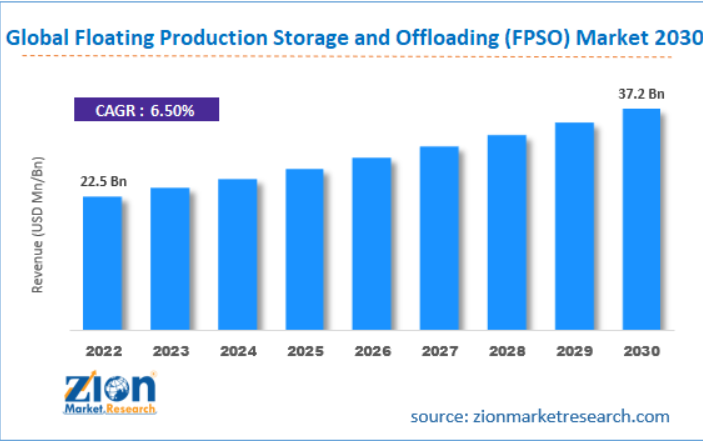

The market for FPSOs is poised to grow at 6.5% per year by the end of the current decade. Image via Zion Research.

The FPSO market is relatively large compared to the FLNG and FSRU markets. As of January 2024, around 270 FPSOs are operating globally. The leading companies are shown in the chart below:

Most of the companies are energy conglomerates. Of the list, only SMB Offshore specializes solely in FPSO management. It is worth noting that most energy companies do not buy FPSOs but enter into operating contracts for a fixed period.

FPSO prices range widely, from around $800 million to several billion dollars. The price is a function of daily production, measured in barrels, and crude storage capacity. The largest FPSO to date is Total Egina (shown in the bottom photo), which was used for the Egina project in Nigeria. Image via Wikipedia.

This FPSO produces 208,000 barrels and can store 2.3 million barrels of crude oil. By comparison, Egina produces the same amount of oil daily as OPEC member Gabon. At the same time, it can store Mexico’s size daily oil production.

Oil rigs are cheaper but have several disadvantages. Unlike rigs, FPSOs have propulsion, so they can move independently. They can also store the extracted crude oil. These two features make FPSO self-sufficient, allowing flexible operation.

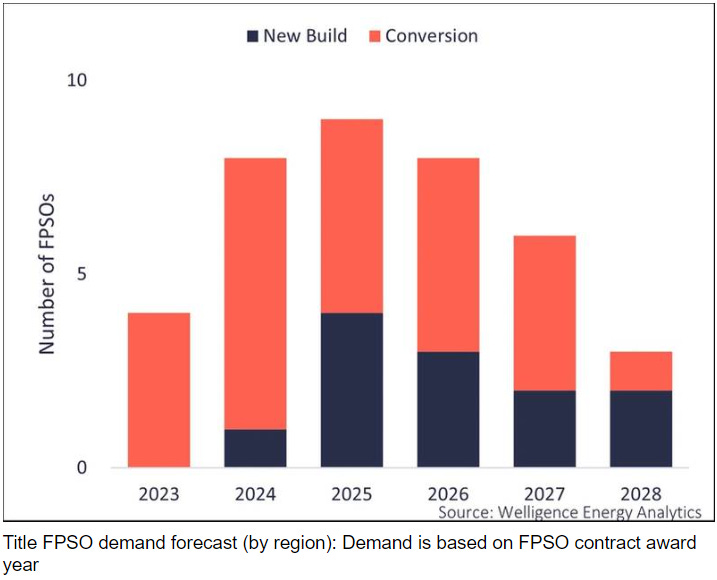

Two ways to build an FPSO are to modify an existing super tanker (VLCC) or start from scratch. The following chart shows the FPSO orders in the coming years according to the production method.

For now, orders for modification of existing tankers cover more than 50% of the total backlog. This fact is important. In the next paragraphs, we will see why.

It is worth mentioning China's role in building hulls for new projects. Factories such as Shanghai Waigaoqiao, Dailan, and Cosco Shipping Heavy Industry are developing mono-purpose hulls that quickly adapt to the FPSO type. On the other hand, Keppel and Sembcorp (now merged into Seatrium) are leading the conversion of supertankers into FPSOs.

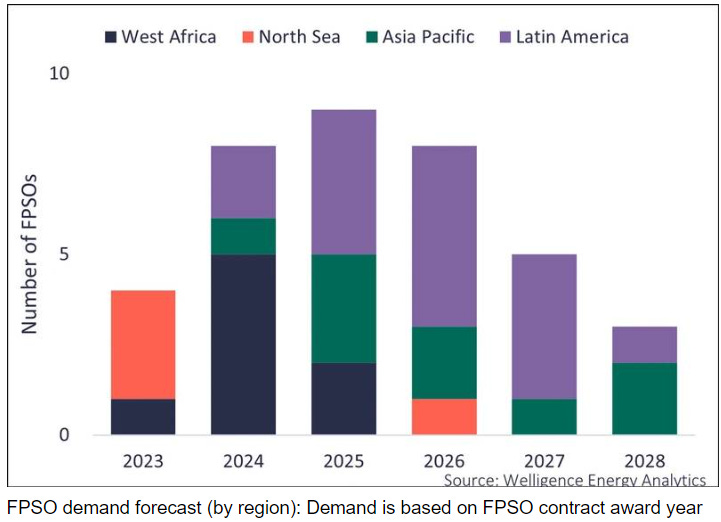

By 2030, over 35 projects will require FPSOs, half of which are planned for Brazil and Guyana. Namibia is the other hot destination. Total, Shell, and Galp Energia actively develop oil fields on the country's shelf. The following chart shows the geographic distribution of new projects requiring FPSOs.

South America and West Africa have become new fossil fuel production hubs. Meanwhile, the North Sea is becoming less attractive. The reasons lie not in the lack of crude oil reserves but in the lack of adequacy in European policymaking. The 'ecology'- based legal obstacles to developing projects in the North Sea continuously put strains on the new projects. Thus, energy companies seek alternatives where they will be welcomed or at least not constantly interfered with.

In summary, the FPSO market depends on deepwater projects. Interest has resurfaced in the last few years, which means there is a demand for FPSOs. Tanker conversions are the primary approach to production; factories specializing in converting supertankers will take more orders. In this case, it is the Singaporean company Seatrium.

FSRU

Now it’s time to talk bout LNG. FPSOs are used to extract crude oil. FSRU and FLNG are built for LNG. The latter is known to the readers. I published a report on Golar LNG in May. The company is the leading operator in the segment.

Uranium and LNG are bets on AI and green energy. That being said, FSRU demand is expected to grow at 6% per year. The driver behind this is the steadily increasing need for natural gas. According to analysts, the annual growth rate is expected to be between 8.5% and 10% by 2030.

The FSRU market is mid-size compared to the FPSO and FLNG. There are currently 45 FSRU plants in operation. The top rank companies in the industry are shown in the following image:

Most of the enterprises are not public. Moreover, they are conglomerates that operate in various shipping segments. Illustrious examples are the Belgian company EXMAR and the Norwegian BW Group.

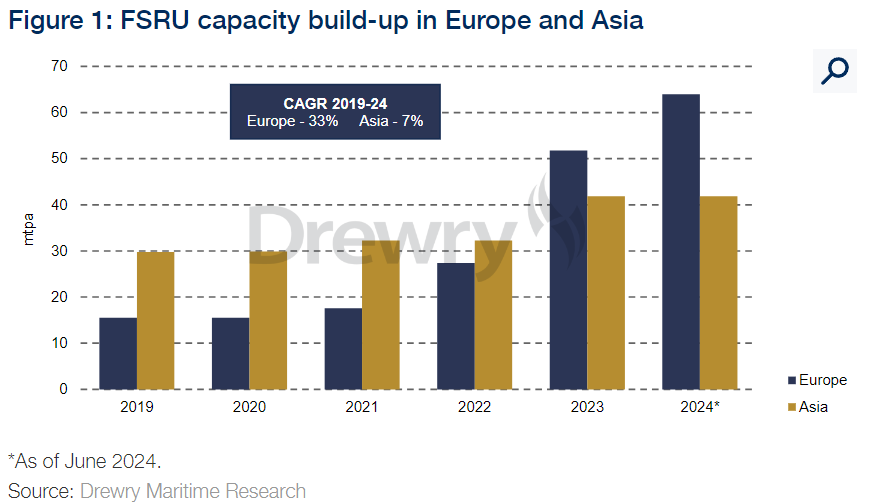

Europe is one of the main drivers of FSRU demand.

Geopolitics is the decisive factor. Europe, the most energy-dependent Great Power, suffers from a chronic need for energy diversification. FSRUs are viable solutions. The Russia-Ukraine war provoked an urgent energy supply shift in the EU. Nine FSRUs have been commissioned since 2022. In comparison, for 2019-2021, only one such plant has come into operation.

Existing FSRUs can also be adapted for other energy sources, such as ammonia or hydrogen. With minor modifications, these can be stored and regasified using existing infrastructure. FSRUs are among the strategic assets that can (somewhat) put Europe back on the world economic map.

What makes FSRUs so attractive?

The following picture illustrates what an FSRU looks like. The largest ship of this class to date is the MOL Challenger. Image via Wikipedia.

It is an LNG carrier upgraded with loading/offloading capabilities. Simply put, an FSRU is a floating LNG terminal that costs much less and is built faster than a land-based one. In comparison, an FSRU with 170,00 cbm capacity costs about $360 million and is built in a few years, while a land terminal with similar features comes out to about $800 million and takes about five years to complete (from design to commissioning).

As with the FPSO, there are two options for producing an FSRU: from scratch, i.e., an entirely new ship, or modifying an existing LNG carrier. The second option reduces the required production time, often under 12 months.

FSRUs are among the most sophisticated vessels, and Chinese shipyards are still lagging behind their South Korean counterparts. As with FPSOs, Seatrium specializes in modifying existing LNG carriers into FSRUs.

Besides Europe, Asia is the other region behind the demand for FSRUs. Apart from major players such as China and India, emerging markets, including the Philippines, Vietnam, and Sri Lanka, are encouraging the development of FSRUs. To date, 20 planned projects in the Far East require FSRUs. This means that prices for new FSRUs will continue to be high, encouraging market participants to opt for conversion.

FLNG

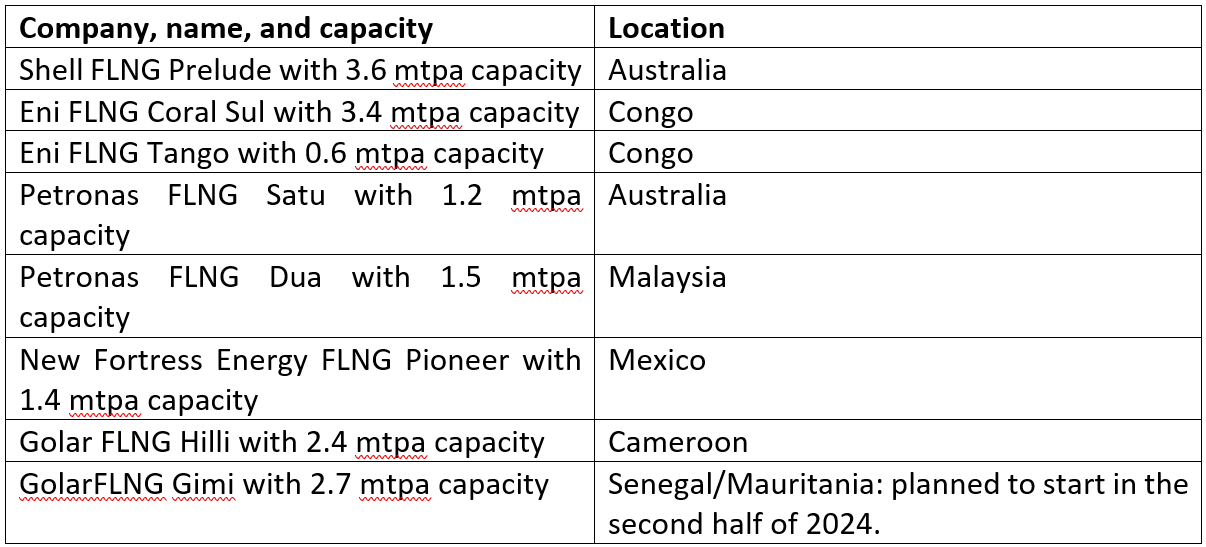

Let’s briefly review the FLNG market. Currently, active FLNG installations are counted on the fingers of both hands (the table is from the Golar LNG report):

In recent months, interest in FLNG installations has grown, judging by the number of projects awaiting or past FID (final investment decision). Samsung Heavy Industries and Wison Energy plan to build several FLNG plants in the coming years. The same applies to established players such as Shell, Eni, and Golar.

Since I published the Golar report in May, there have been no changes in market dynamics. Demand for non-FLNG continues to increase. However, the interest in smaller FLNG plants with a capacity of 1 to 3 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) is worth mentioning.

Small and medium FLNGs with 1-3 MTPA capacity cost between $1.5 and $3 billion. In comparison, Shell's Prelude FLNG (3.6 MTPA capacity) has reached a total cost of $10 billion and has been under construction for over five years. Prelude was the first designed, built, and commissioned FLNG, which explains the colossal cost. Production lines were custom-made, which costs considerably more time and effort, i.e., money.

It has been 12 years since then (Prelude began construction in 2012). Shipyards developed its know-how, so even projects of this scale won't cost $10 billion. However, that doesn't mean small and medium-sized plants aren't more competitive.

They can be built with a modular design, resulting in lower final costs because production is closer to serial. Standardizing the construction avoids extensive custom design and modifications required for single vessels like the Prelude.

To be profitable, large FLNGs are employed for the largest gas fields. Otherwise, capacity utilization could decline, meaning losses. Small and medium-sized plants are perfect for fields considered uneconomic due to fewer oil and gas reserves.

Europe (including Bulgaria), Southeast Asia, and East Africa have numerous smaller gas fields. Thanks to the small FLNGs, its exploitation is economically plausible.

As with the FPSO, an FSRU could be built in two ways: building from scratch or modifying an LNG carrier. Korean plants lead in the first category, and Seatrium in the second.

Companies’ decisions on FSRU/FLNG production depend on another factor—the LNG carrier propulsion system. Over 15% of the world's LNG fleet has steam turbines. They are obsolete and inefficient, and as such, they do not meet the exhaust emission standards imposed by MARPOL. Steam turbine LNGs will soon be forced out of service. There is one exception—ice-class gas carriers. However, they represent a small fraction of all steam turbine-equipped LNG carriers.

Old steamers may have a future as FLNG plants. An example is Golar LNG and its Fuji gas carrier. Fuji is planned to be modified to FLNG. Viewed from a higher perspective, the increasing number of steam turbine ships proposed for FLNG leads to more orders for specialized shipyards.

To recap what has been said so far. A shipbuilding capacity deficit is growing due to the following reasons:

At this stage, shipyards are focused on container ships, gas carriers, and car carriers. Tankers, bulkers, offshore supply vessels, and complex plants are at the back of the queue.

South Korea's demographics, combined with its conservative immigration policies, are becoming an acute problem for the country's industry. The same is true for Japan.

Demand for FPSOs, FSRUs, and FLNGs will grow significantly in the coming years due to factors such as AI, energy transition, demographics, and geopolitics.

For now, the priority is on vessels’ conversion from cargo ships into floating energy assets. Hence, shipyards specialized in vessel modifications will be highly demanded.

As mentioned, Seatrium is among the leading companies offering ship conversions (tankers and gas carriers) to floating energy assets. That being said, let’s move on to our AI/Clean Energy builder of the day.

Seatrium Limited

Seatrium Limited was formed in 2023 from the merger of Sembcorp Marine and Keppel Offshore & Marine. The company's shares are listed in Singapore and Germany. However, Seatrium Limited's history began long before the merger.

Keppel is an established player in oil rig construction. Temasek, an investment company owned by the Singapore government, incorporated Keppel. Temasek also owns 37.9% of Seatrium's shares. Keppel's name has a curious history. It derives from the name of Henry Keppel, a British captain who discovered Tanjong Pagar Bay. The bay was later renamed after its discoverer.

The Proclamation of Independence of Singapore was declared in 1965. In 1968, Keppel Harbor came into the country's possession when the company of the same name was established. Temasek and Keppel thus became among the country's main economic drivers.

Keppel developed interests beyond the maritime business. Accordingly, the company set up subsidiaries that specialize in various activities. In 2001, several of these companies were merged under Keppel Offshore.

The other half of the equation, Sembcorp Marine, is part of Sembcorp Industries, another of the conglomerates owned by Temasek. The company specializes in energy and construction. In the 2018-2021 period, Sembcorp Marine recorded massive losses. The reasons, of course, are not only in the company. This is the period when the Green Cult reached peak levels of stupidity, and anything to do with fossil fuels was classified as the ultimate heresy. Separately, in 2020, the C19 event occurred. In turn, energy companies have to struggle for their survival.

That is not to detract from Sembcorp Marine's internal problems. Rather, it is reminiscent of the power of the 50/30/20 principle: the big picture shifts and the industry trends predetermine a company's bottom line more than business processes considered in isolation.

And so on until 2023, when Sembcorp Marine acquires Keppel Offshore & Marine. In my view, the timing of this merger is more than reasonable. As I said in the introduction, demand for floating energy assets has yet to grow. And Keppel and Sembcorp have a track record of building such installations.

The 2023 results are telling. I present a sampling of Seatrium's accomplishments for the past year:

Gimi - the second FLNG to Golar LNG conversion project for the GTA (Greater Tortue Ahmeyim) field located offshore Mauritania and Senegal;

FSRU Energos Celsius - FSRU conversion for New Fortress Energy (NFE) for deployment at NFE's LNG terminal in Barcarena, Brazil;

FSRU Alexandroupolis - conversion of the first Greek FSRU for GasLog Limited;

Almirante Tamandare - a project to manufacture modules for the topside of an FPSO delivered to SBM Offshore for final deployment in the Búzios field in the Santos Basin, off the coast of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil;

FPSO Leopold Sedar Senghor - FPSO completion project for MODEC, owned and operated by Woodside Energy, for the Sangomar field, Senegal's first offshore oil field;

BW Opportunity - modification and upgrade of FPSO for BW Offshore.

The above list shows a few things: first, that the company is prioritizing complex energy installations; second, that the customers are established names in the industry; and third, that the customers are geographically diversified.

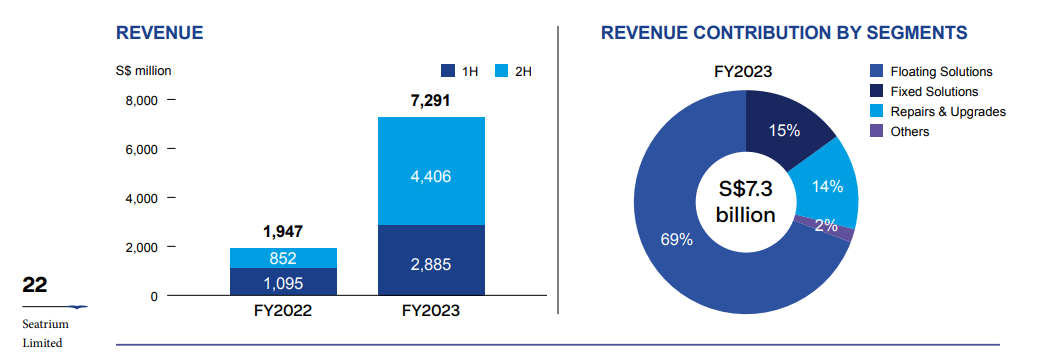

The distribution of revenue by themes looks like this.

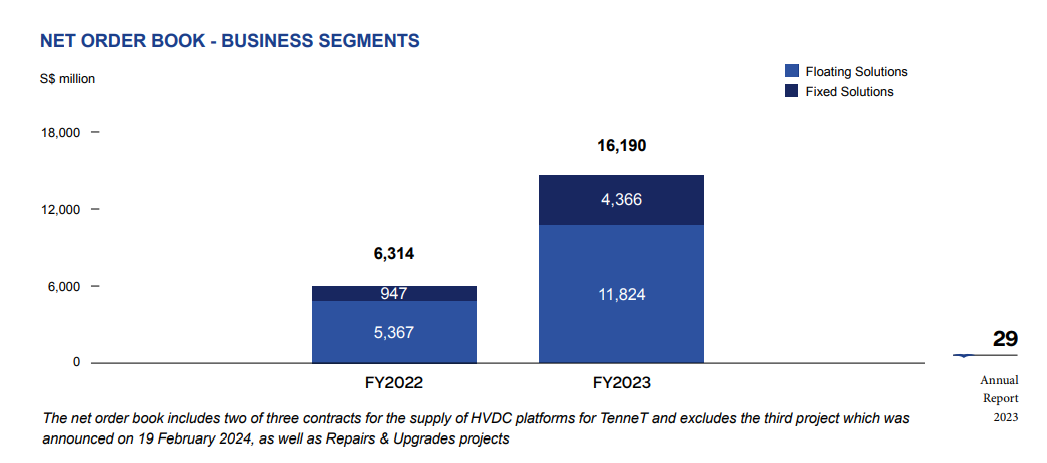

69% of revenues come from floating solutions, i.e., FPSO, FSRU, and FLNG. The remaining 31% is split between fixed solutions (offshore renewables installations) and vessel repairs. The company's backlog is similarly distributed - 72% floating solutions and 26% fixed solutions. FY23 orders are for $16.190 billion, three times the company's capitalization and more than double its 2023 revenue. It is worth noting the increase in orders by segment. Fixed Assets realized 350% growth over 2022, and floating assets 121%. Overall backlog growth is 158% in 2023 versus 2022.

The chart below shows the Seatrium 2023 backlog:

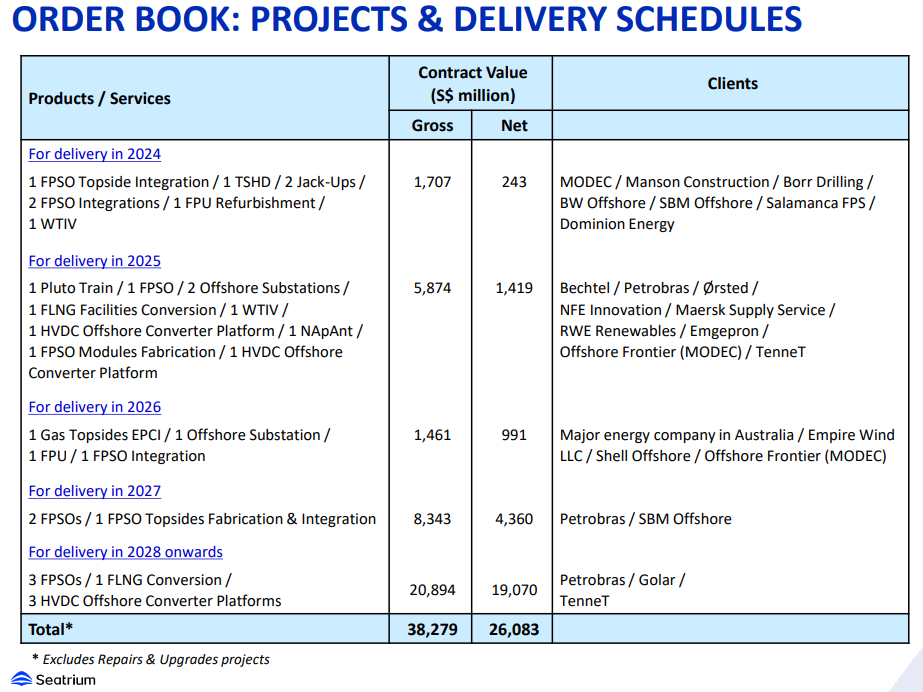

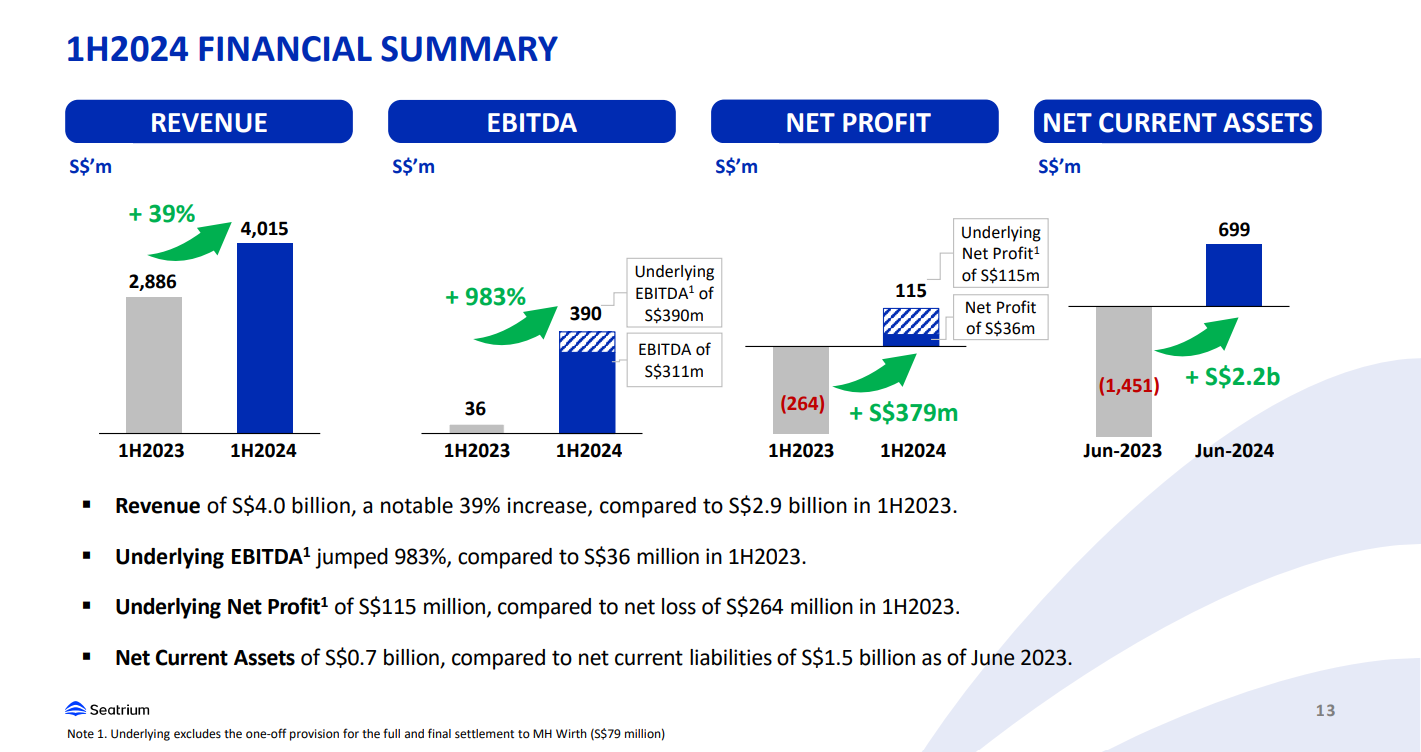

Judging by 2023 orders, I expect the Backlog to grow even more this year. The company's latest report, released today, August 02, 2024, confirms my observation. Seatrium recorded a $26 billion 1H24 backlog.

The table below shows what the company's orders look like to date:

Since May this year, Seatrium has been in the news due to Petrobras's $11 billion order to build two new FPSOs. P-84 and P-85 units will be dispatched in the Atapu and Sepia fields in the Santos Basin. The units have a planned production capacity of 225,000 barrels of oil per day and a gas processing capacity of 10 million cubic meters per day. Construction will begin in early 2025, and delivery is expected in 2029. Seatrium's facilities in Brazil, China, and Singapore will produce 60,000 tonnes of modules for the FPSO, with integration and commissioning to be carried out in Singapore.

On 05 July 2024, Seatrium entered into a contract with Greek shipping company Angelicoussis Group to retrofit its LNG carriers, tankers, and bulk carriers. The corporation in question owns Maran Gas, a large LNG carrier operator with 45 vessels. The order involves refitting 10-15 ships a year. At this stage, the contract amount has not been published.

An order from Hyundai LNG Shipping is a testament to the quality of Seatrium's work. Instead of awarding the contract to Hyundai Heavy Industries, the company contracted Seatrium to repair and upgrade its LNG carriers.

In 2023, Seatrium successfully retrofitted the world's first ammonia and diesel-capable ship, the FFI Green Pioneer, for Fortescue Future Industries. The proof-of-concept project involved installing the entire gas fuel delivery system and converting two of the four engines to enable the ship to run on ammonia and diesel. The trend towards alternative fuels in the marine industry is an investment theme worthy of special attention. An example is ammonia carriers, or VLACs, very large ammonia carriers.

As Seatrium’s technical achievements show, I expect the company to solidify its position as an established builder of floating energy assets. That translated into a growing backlog, higher revenues, and improved profitability.

Balance Sheet and Efficiency

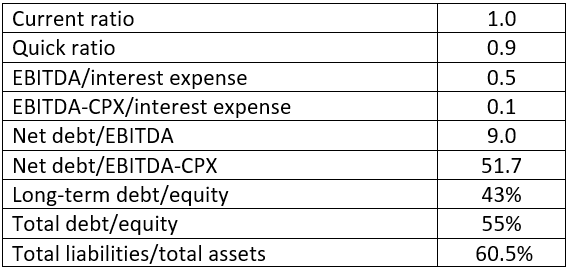

Shipbuilding is among the most demanding businesses. The ups last shorter than the downs, meaning that a shipbuilding company's survival is always at stake. In this case, the first line of defense is a strong balance sheet.

Seatrium maintains adequate solvency and liquidity, ensuring company survivability. The total debt is half of the company's equity. Judging by the liquidity criteria, there is room for improvement. Yet Seatrium has been generating substantial free cash flow, higher than the interest payments for two years now.

Notably, Seatrium reported $4.12 billion in intangible assets, almost a third of its total assets. One reason is the Goodwill of $3.8 billion, which resulted from the deal between Sembcorp Marine and Keppel Offshore & Marine. In 2023, the company realized a loss due to significant non-operating expenses - write-off of provisions and no core assets, merger costs between the two companies, and settling legal claims, all related to the merger.

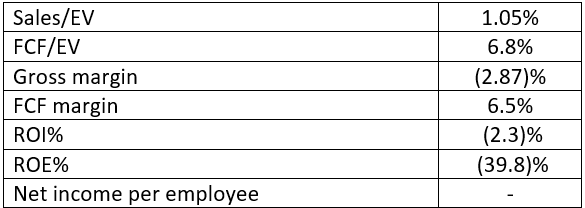

The following table presents several metrics reporting the business's performance based on 2023 data.

Since Seatrium did not generate a net profit in 2023, the rate of return is negative. However, the company delivered positive free and operating cash flows.

The following graph shows Seatirum's results for 1H24.

Revenue was up 39% from 1H23, and the company realized a net profit. The three most important variables to me are the increase in orders to $26 billion, rising revenues, and free cash flow. Over the long term, these three factors determine the effectiveness of any capital-intensive business's survival.

Valuation

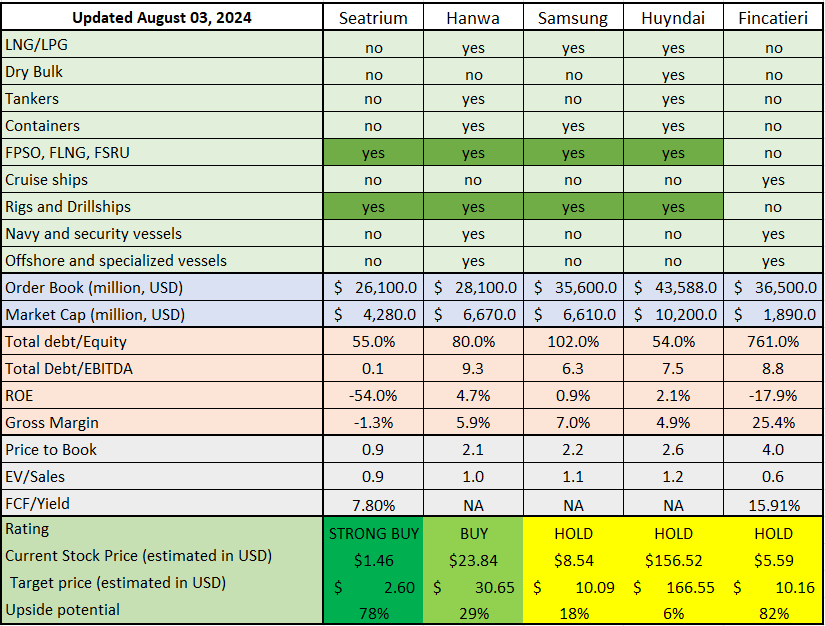

Unlike shipping companies, where the valuation of net assets is straightforward, this is not the case for shipyards. The reason is that there is no readily available data on shipyard values. Therefore, I use comparative valuation with multiples, Price to Book, EV/Sales, and FCF Yield.

To compare Seatrium, I picked Hanhwa, Samsung, Hyundai, and Fincantieri. The latter mainly produces passenger ships for companies like Carnival (Carnival Plc) and vessels for the Italian Navy. I have deliberately included it because it gives additional context to comparing the shipyards. I am not a fan of Fincantieri because it produces wants, not needs. This makes the already turbulent business of shipbuilders even more extreme.

Unlike Fincantieri, floating energy assets are needs, not wants. Energy is the foundation of our material world. Without another Carnival cruise vessel, the economy would continue functioning; however, energy security would be questionable without FPSO Egin or MOL Challenger. As I noted earlier, Europe knows best what is at stake.

The following table summarizes everything said so far.

It is divided into four sections:

Production capacities: what vessels the shipyard can build.

Backlog and market capitalization: revenue predictability and current market valuation.

Finance: solvency, liquidity, and efficiency.

Valuation: Price to Book, EV/Sales, FCF Yield.

Summary: rating, target price, upside potential.

To determine the target price (take profit), I use the company's multiples relative to the 10-year industry average as inputs. I consider EV/S and Price to Book to be equal because the ability of the shipyard to generate revenue is at least as important as the company's book value. I have deliberately excluded FCF Yield from the equation because Seatrium is a new company, while the others are much older. So, the comparison would not be objective.

Seatrium offers the most for its current price. Unlike the big three, who build (almost) everything, the company specializes in floating energy assets. Accordingly, Seatrium is a proven leader in converting ships into floating energy assets. In other words, Seatrium owns the mythical moat.

If a company comes with ten billion in spare cash and decides to build a shipyard for FPSO, FSRU, and FLNG, it will fail because money will provide tangible assets but not the skilled workforce and know-how to run such an enterprise. Experienced shipbuilders and management skills take years to nurture. What has been said applies to all shipbuilders on the list. They have decades of history and have established themselves as leaders in their niches.

Technical Analysis

Seatrium's chart is similar to that of a company in bankruptcy awaiting restructuring.

The current price brings an opportunity for entry with a small volume and a stop loss of around $1.30 (the local bottom from three weeks ago). With a take profit of $2.6, a stop at $1.3, and a buy price of $1.5, we get a risk reward of 5.5.

If the price successfully breaks the local peak of $2.0, there is a high chance of passing $3.0. Companies’ shares trading for cents or a few dollars often make x5 movements in a couple of months in the presence of a catalyst event. In Seatrium's case, it would be another order of Petrobras scale or a radical change in the industry. By the latter, I mean closing some of the plants in South Korea and shifting away their focus from floating energy assets. The first scenario is very likely, while the second is potential but not plausible.

Risks

Seatrium faces the following risks:

Liquidity risk

Market risk

Economic risk

I start with the risks that are (almost) nonexistent. The political risk in Singapore comes to mind. The state is doing its prime job of not interfering with the business. I also consider the operational risk minimal because the two companies creating Seatrium have years of experience in the industry, so they know a thing or two about shipbuilding.

Of the available risks, the most serious is the economic risk. In recent days, negative data on the US economy have come out. They do not spell the end of the world but probably suggest a cooling of the economy. Yet sometimes, bad news for the economy is good news for the markets.

Fear of a recession will provoke the Fed to lower interest rates urgently. Moreover, an election is coming, a reminder that the Fed is neither federal nor reserve but a political institution serving the incumbent. The Democrats will do everything they can to win the election.

I am not confident that another rate cut is the best solution in the long term. Remember, prudent economic measures and political propaganda do not stand in the same sentence, just as oil does not mix with water. So, interest rates will most likely be lowered, temporarily calming market participants. Meanwhile, the economy is fine…until it is not. And that brings me to the next risk—the market risk.

Currently, the markets are moving on thin ice. The Fed is one of the most important known unknowns. For now, a rate cut in September is highly probable. However, there is another factor—how many points the cut will be. Hasty and excessive actions may spark inflation. The opposite is true, too: an insufficient rate cut would have no tangible effect. Nevertheless, investors are well-trained Pavlov’s dogs. Anticipation of rate cuts may reignite the bull trend, at least for a while.

Financially, the company is performing well. Debt levels are low, and the company will most likely be able to cover its debt payments in a crisis. The numbers are telling. Seatrium holds $1.72 billion in cash while owing $2.69 billion in total debt. Even in case of a global recession, Seatrium will weather the storm.

Conclusion

Where to invest?

Macro: Demographics, geopolitics, AI, and green energy all mean an increasing demand for cleaner energy. It is impossible to have both at the same time: sufficient energy and zero emissions within a decade. However, a middle path exists, satisfying energy needs while producing fewer emissions. The solution is uranium and natural gas.

Region: Singapore is among the countries with the lowest political and economic risk.

Industry: companies that produce floating energy assets. Only a handful of shipyards are capable of building such assets worldwide.

Company: Seatrium is a rare find because it combines distinct moat (specific know-how and tangible assets), solid financials, earnings growth potential, political certainty, and a low relative valuation.

Why invest in Seatrium?

Balance Sheet: Seatrium maintains excellent solvency and liquidity despite the net loss from 2023.

Efficiency: The company has yet to show its strength, judging by the enormous backlog and 1H24 strong figures.

Dividends and buybacks: at this stage, the company does not distribute dividends or plan to repurchase shares.

How much am I paying for Seatrium's business?

Business valuation: due to the peculiarities of the shipbuilding business, a valuation based on net assets is (almost) impossible for a person without access to databases with shipyard valuations. At the same time, a valuation based on discounted cash flows is frivolous for a highly cyclical business like shipbuilding. These factors limit the choice to a comparative valuation based on multiples.

Benchmark: Seatrium trades at low multiples compared to the big three of South Korea and Fincantieri. The situation is the same when compared to industry averages. The company offers almost 80% growth potential relative to the current market price.

When to buy?

Technical analysis: the price is at the bottom, and this is an excellent buying opportunity with a close stop loss and high-risk reward. With a take profit of $2.6, a stop at $1.3, and a buy price of $1.5, we get a risk reward of 5.5. However, let's not forget that bottoms, unlike tops, last longer than most expect (and would like). So, the current price is an opportunity to enter with a small percentage of the intended volume for Seatrium. Accordingly, increase volume on a successful breakout of significant price levels.

Catalyst events: another order of the caliber of the Petrobras contract, technical difficulties with South Korean competitors, and an escalation on the Korean peninsula between South and North Korea.

How much to buy?

Kelly's formula is a risk/reward ratio of 5.5, a time horizon of 18-24 months, a share in a portfolio of 15-20%, and a position risk of 3.2-6.4%.

Everything described in this report has been created for educational purposes only. It does not constitute advice, recommendation, or counsel for investing in securities.

The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the author and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to do your own research and discuss your investments with financial advisers to understand whether any investment suits your needs and goals.

Full disclosure: I do not hold a position in Seatrium when publishing this article. Note that this is a disclosure, not a recommendation to buy or sell.

Great article. Very thorough.

BEZ.SI is a small player in this space. Moving to an asset lite business mainly refitting and maintaining FPSO's