I'm writing about neurobiology, discipline, and the Delphic Oracle today. Don't worry; you are still in The Old Economy.

How we look at life and our physiology determine results in every endeavor. Investing is no exception. What does it take to become a successful investor? To turn our backs on economics and finance and become neurobiologist philosophers?

To some extent, yes, without ignoring the importance of knowledge of economics and finance. They are an absolute must for any serious market participant. But they are the smaller piece of a much larger puzzle - that of knowing ourselves. And the missing pieces are not found in macroeconomics and accounting textbooks.

We are what we think. The quality of our thoughts determines the quality of our decisions, actions, and consequences. If we are mediocre in our thoughts, our actions and results will inevitably be mediocre.

Every thought is a program command. The set of commands creates a program, i.e., a habit. A set of programs operates in an operating system. Our operating system is our profound beliefs about money, society, life, and death.

Where are these programs stored? In our brain. We still know too little about it, yet some of its physiology is well-studied. It is divided into the reptilian brain, the limbic system, and the neocortex. This is our hardware. As such, it has characteristics that we cannot change.

Unlike hardware, we can control our thoughts. It's up to us how we interpret what's happening around us, what we expect from the world, and who we hold responsible for our destiny—ourselves or everyone else.

The quality of our thoughts is determined by the information we consume. When we consume information junk food, we cannot expect our thoughts to be anything more than mediocre. And so the cycle is set in motion—mediocre thoughts, mediocre decisions, mediocre actions, and mediocre results. For me, mediocrity is incompatible with success in the markets and life.

Mediocrity thrives in our comfort zone, where we follow the path of least resistance, being mediocre in our thoughts for another day but expecting something different from tomorrow. We think and act the same way, hoping for different results.

In a series of two posts, I aim to get the readers' interest in themselves. They should turn inward and ask what they want and what price they would pay. In my quest to achieve it, I seek the answers to a few questions:

· What role does physiology play in our journey as investors?

· Which is more important - the ability to learn or unlearn?

· What are the necessary qualities for an investor?

You will not find a shortcut to successful investments in today's article. However, there is one that is so close yet so far: ourselves.

After reading the article, you will most likely have more questions than before. If so, I have achieved its purpose.

Neurobiology for investors

This point is dedicated to our physiology. We are slaves to the nerve impulses that run through our brains. And they are a response from the biochemical mess of raging hormones triggered by external stimuli.

The human body is highly complex and cannot be described in volumes of books, much less in a few paragraphs on an investment blog. However, as investors, we must know our hardware and its parameters. In the following lines, I set myself the difficult task of introducing you to our brain.

Our physiology, to a large extent, determines emotional intelligence and the ability to learn. At the same time, both are subject to cultivation within the framework set by physiology.

In financial markets, emotional intelligence is more critical than our cognitive intelligence (the mythical and overrated IQ). An emotionally stable market participant with sufficient but not brilliant analytical skills will beat a brilliant analyst who is emotionally unstable.

When we learn, we physically change. Frequent repetition of the same action improves the efficiency of our nervous system. Meta-learning, learning how to learn, is a must-have skill for anyone deciding to build a career in the markets.

After this introduction, let’s move to the topic of dissecting the structure of our brain.

Amygdala, thalamus and emotional intelligence

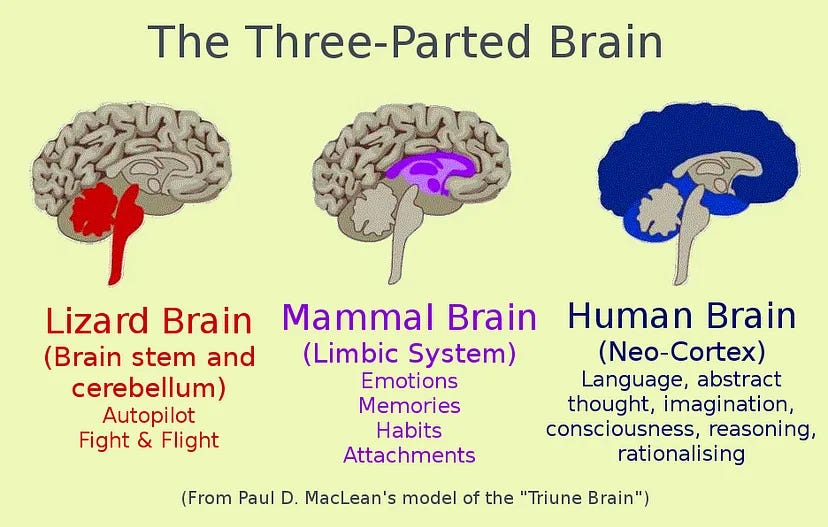

To a large extent, emotional intelligence is a function of the structure of our brain. According to McLean's triune brain hypothesis, the contents of our cranial box consist of three main compartments:

· Reptilian brain - responsible for our primary instincts, feeding, security, and reproduction. This part of the brain is the ancient legacy of the dinosaur era. It works in two modes - fight or flight.

· Limbic system - the part responsible for our emotions, i.e., how we react to environmental changes. This is the "mammalian" brain inherited from our furry relatives.

· The neocortex - the part responsible for our cognitive abilities. The neocortex physiologically distinguishes us from all other vertebrates, including mammals. The presence of the neocortex makes possible the emergence of abstract thinking, logic, and creativity.

Which of the three parts determines our behavior the most?

As much as we don't want to admit it, the neocortex plays the most minor role in our daily lives. In other words, we obey impulses from the limbic and reptilian brain.

The amygdala, thalamus, and hippocampus are located in the limbic brain. The thalamus perceives sensory information, which it relays to the amygdala. The latter is our detector for imminent dangers. The amygdala retrieves the input data to detect the presence or absence of factors threatening our lives. The hippocampus is our archive where we store information about past experiences.

In milliseconds, the amygdala checks with the available data in the archive (hippocampus) whether there is danger in the environment. In parallel, the amygdala sends information to the neocortex for further analysis. And here comes the exciting part.

First, the connection between the hippocampus and the amygdala is significantly faster than between the amygdala and the neocortex. Second, when the amygdala recognizes danger on the horizon, it cuts off the flow of information coming from the neocortex. Thus, we have transformed from logical-thinking individuals into reactive creatures, subjugated to the limbic brain. In neurobiology, this process is called "amygdala hijack" (AH).

We have all been victims of it, including in the markets. An example of AH is when we see a losing position, become paralyzed with fear, and don't know what to do. Another example is when we see a small profit and rush to close it. In both cases, our actions are subordinate to the amygdala.

The three brains are in a constant relationship. However, as we have seen, it is not equal. Also, the nerve cells between the amygdala and the neocortex are asymmetrically distributed but not in our favor. From the amygdala to the neocortex, 80% of the nerve endings are directed, while in the opposite direction, only 20%.

In other words, the reactive/unconscious part of the brain broadcasts 80% of the information (commands) to the proactive/conscious part. Correspondingly, the neocortex directs four times less information to our unconscious part.

The next time you are in a stressful situation, think about the source of your reaction - the neocortex or the other two lobes. Most likely, it will be just them. This mode of operation has ensured the physical survival of our species over the millennia.

Our physiology is still adapted to life in the wilderness, where everything is black and white - life and death, satiety and hunger, hot and cold. In all the millennia of technical progress, we have not changed physically. We remain the same slaves to biochemistry as the African savannah's inhabitants 10,000 years ago.

Financial markets in their modern form have existed for the last five centuries. In the current era of hyper-information, they have been around for 30 years. There is an apparent dissonance between the environment (the information age and financial markets) and the protagonists (irrational beings subject to physiology). That's why most people are not successful in markets in the long run—the mismatch between the environment and the missing qualities of market participants cannot be compensated for ... in most cases.

I say most because there is still hope. We must learn to be adaptive and resilient. It is not an easy task because we are up against ourselves.

We cannot change the structure of our brain, but we can train ourselves to resist its commands. When we fall into an AH state, we must remain proactive. This is the only way we will consciously choose how to react. If we do not master our reactions, our reactions become our masters. In other words, we remain reactive and have no choice. The amygdala takes the charge.

Adaptability and resilience are trained in only one way—in a stressful environment. Since we are talking about financial markets, this means opening a real account as soon as possible. Demo accounts teach bad habits, which we only learn about when we start with real money. Our brains understand very well when a bet is real and when it is not.

Just as in combat sports, we are used as a punching bag, not briefly; in the markets, our path to success goes through a lot of emotional pain. Our task is to learn to react consciously when we are pressured by the limbic brain, which causes us to act NOW.

While there is no shortcut, there is still a path.

There is a difference between knowing the path and walking the path.

Morpheus

So far, we have learned that our physiology works against us in the markets and that the road to adaptability and resilience is long and thorny. Now comes the good news, or at least the not-so-bad news. We'll see that our brains aren't so unsuited to the markets as long as we know how to work with them. It's about myelin and intuition.

Myelin and intuition

A word is often used as a synonym for the sixth sense. It is mentioned when someone solves instantly an "unsolvable" problem. It occurs episodically and is not a product of our conscious control. These characteristics make it abstract and challenging to describe. In the following lines, I will try to explain the inexplicable.

Quantitative accumulations * time = qualitative changes = Intuition

Intuition is a high-order understanding.

To the extent language's limitations allow, the extended definition is this: intuition results from quantitative accumulations that have led to qualitative changes that lead to high-order understanding.

The more time and effort we put into something, the better we get at it. Our skills and knowledge eventually make a qualitative leap. We've done action XYZ so often that we no longer have to consciously analyze, think, or decide—we absorb the information and instantly convert it into working hypotheses.

Intuition is a consequence of physical changes in our brains caused by the effort and time spent learning new skills. When we learn and practice, we change our brains qualitatively and quantitatively. As we develop new skills and knowledge, myelin accumulates around the nerve cells.

Myelin is an insulating tissue covering our neurons. It acts like insulation on a conductor. The thicker the insulation, the less signal loss, resulting in cleaner and more robust signal transmission between neurons.

How is myelin associated with learning new things?

Learning new things can be boiled down to the efficiency of the neural networks that make up our brains. Excellence in skill in a particular discipline is directly proportional to the amount of myelin surrounding our neurons. The accumulation of myelin happens only one way - with constant learning and a lot of patience. There is no short and easy path leading to maximum results.

The legend of Soros and his physical signals is an excellent example of the practice-myelin-intuition relationship. Many traders would ignore headaches and backaches, but for Soros, they were a sign that it was time to change his view of the market. Sometimes, that even meant taking a position opposite to his current one.

Back pain is like the residual waves caused by a pebble thrown into a pond. Soros' thought process in the context of financial markets proceeds qualitatively differently than the majority.

This is also a consequence of the accumulated myelin in its neural networks, which operate faster. Most investors operate under a 2G signal, while Soros operates in a 6G network. The accumulation of myelin between neurons at one point leads to physical changes.

In the above example, we can replace Soros with legendary figures from every other field. General Patton, Kobe Bryant, and Kasparov are all extremely good at their work. Due to endless hours of practice, their brains differ from the majority. These physical changes lead to episodic manifestations of intuition—a direct perception of reality of a higher order.

Consistency is the key to achieving intuitive skills. The more we practice consciously, the more we change our brains. Intuition comes with experience gained through endless repetition of trial and error. The result is mental models of markets that we integrate so profoundly that they become part of us. When needed, they are automatically and unconsciously activated. To put it another way - we gain insight.

At this point, we realized two things about our brains: they love to command and learn. We have two tasks—to take back control and to keep learning. Both are complex, painful, and often dull pursuits. But if it were easy, everyone would be a Soros, Kobe, or General Patton.

Enough with the neurobiology. In the next part, I share my philosophical perspective. I promise to disappoint those seeking the holy grail of investing. If there is one, it is ourselves—Recall Po's image from the introduction.