Philosophy for investors

Learning and unlearning, curiosity and discipline, responsibility and resilience

We cannot change our physiology, but we can control our reactions. The same applies to our thoughts, expectations, and attitudes. Today, it's the turn of the philosophical sequel in the series about neurobiologist philosophers who venture as investors.

We are the sum of all our decisions, both made and unmade. By dwelling on one option, we miss countless others. The decisions we do not make define us at least as much as the ones we make.

That doesn't mean we shouldn't think about the decisions we make. On the contrary, we should analyze our decisions, actions, and their consequences to understand what works and what does not work for us. That way, we will know what we need to change.

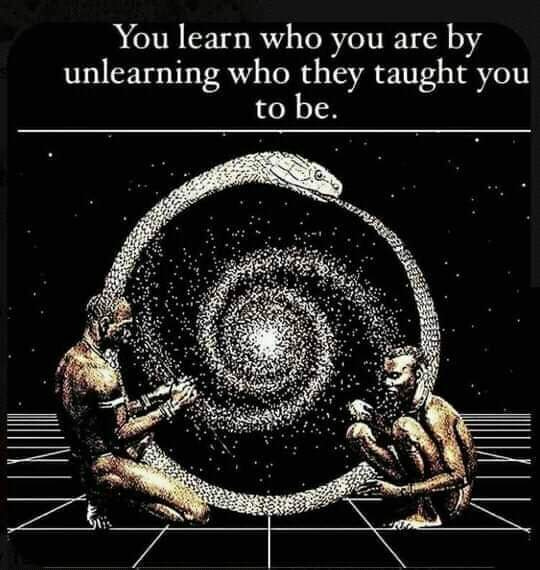

And here comes another catch. We think learning new skills and gaining knowledge are necessary and sufficient conditions for progress. That is a valid statement, but only to a certain extent. First, we should eliminate harmful habits and then acquire new ones.

Unlearning is the first mandatory step, but it does not replace the next step, learning. The education system claims that we all learn similarly, which is a wrong assumption. We learn according to our cognitive and emotional characteristics, predetermining our market approach. One shoe size does not fit all.

And what skills and qualities should a market participant have? Calculate discounted cash flows by heart and be able to quote every balance sheet read or if it is something else. The ones listed are useful, but technical skills are a consequence of something else. It's about the qualities we build over the years.

Unlike technical knowledge, they are cultivated over a long period and only with practice, i.e., in a stressful environment. We do not learn to invest by reading about investing, although that is the first obligatory step. We need to get a financial slap in the face to get how much we don't know that we don't know.

Today, I'm reasoning about unlearning, discipline, and the Oracle of Delphi. But before I discuss the skills and qualities we need to survive in markets, let's examine the types of market actors.

Types of market participants

Our cognitive and emotional traits largely determine what kind of market participants we are. And not in the context of losers and winners. There are countless ways to lose money in the markets and far fewer ways to make money. However, a little does not mean one way. Of the few workable ways, we must first rule out the unworkable ones. Only then (probably) will we find our way.

I can classify the types of market participants according to:

· Time horizon - day traders, position traders, and buy and hold investors; the time horizon also determines the frequency of trades

· Market characteristics - volatility, value, trend

The time horizon depends on our tendency to wait, that is, to stand and do nothing. Some people need more action, while others need less. At one end of the scale are the scalpers with dozens of trades daily, and at the other are the "buy and hold" investors with a few trades a year.

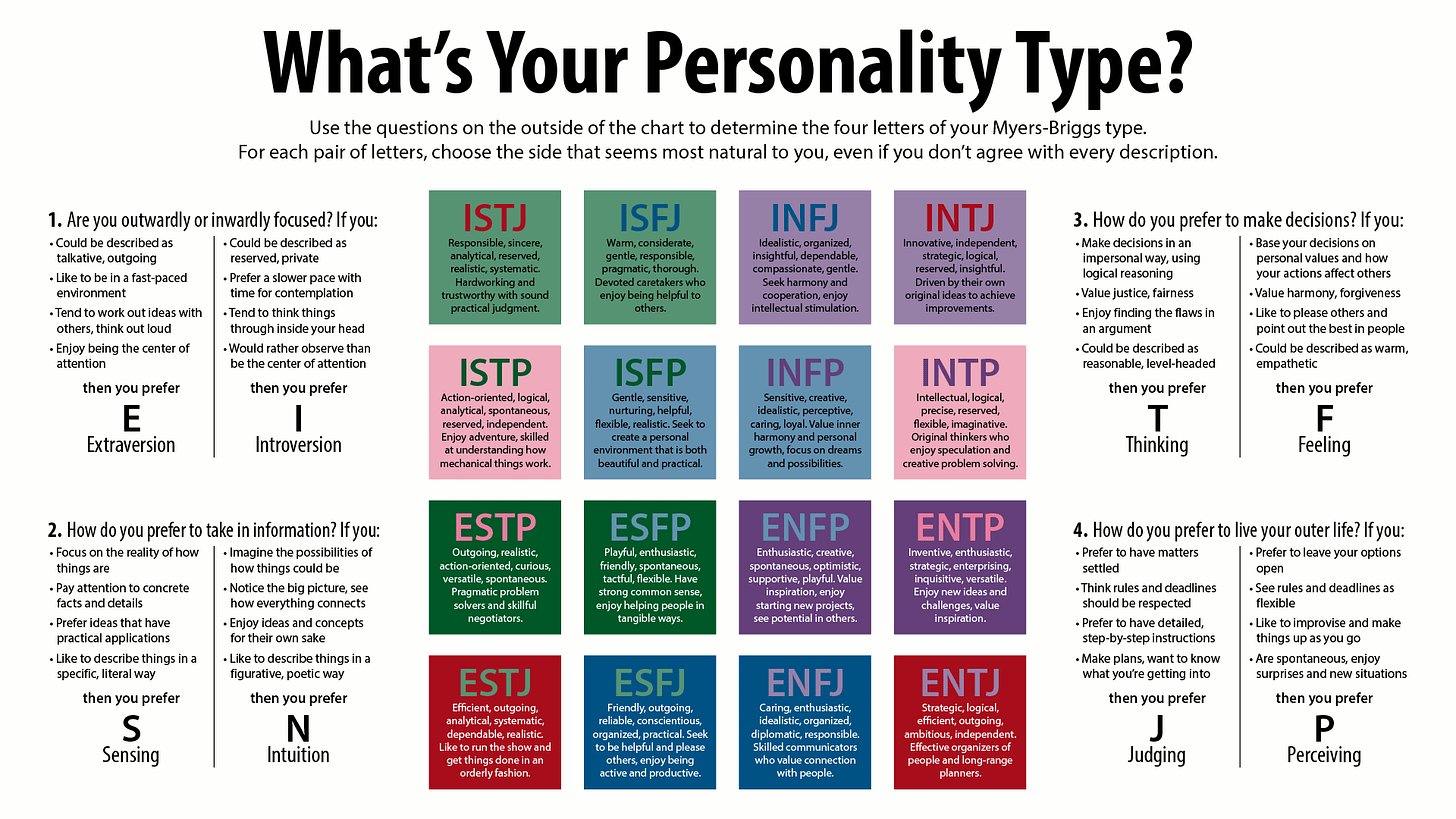

The market characteristics we exploit are a function of our personality typology. Each of these characteristics may or may not fit different types of market participants. It is preferable to exploit the one that resonates with us rather than vice versa.

I give an example of myself—I am an INTJ type according to the Myers-Briggs typology. In simple words, I would say I am a boring, introverted nerd.

As such, I don't like too much action. At the same time, I prefer the infrequent but intense action that I have long prepared for. I take trades with a 12-18-month horizon to take advantage of value and volatility.

That's why old economy companies fit me so well. They are distinctly cyclical, often trading for cents on the dollar of net assets at the bottom. At the same time, they are highly volatile in both directions. That's an advantage for me because I'm chasing double-digit alpha, and volatility is the entry fee for the opportunity to get it.

I remind you that there are no better or worse categories among the ones listed. Some suit us, and those that do not. Approaches that do not resonate with us are not just useless; they can destroy our emotional and financial capital.

I know this from experience. When I started my adventure in the financial markets, I stubbornly went against myself. I insisted that I had to be a day trader, and no matter how hard I persisted, it didn't work. Then I tried the other extreme—something like "buy and hold" with a minimum of trades per year. It turned out that wasn't for me either.

In the first case, I lost not just financial but emotional capital. Burnout was my normal mental state. Buy-and-hold didn't fit my mentality either because it was too dull. As I said, I like periods of calm interspersed with intense action. I gradually got closer to what fits my mentality by rejecting what didn't work.

As you can see, we remove the fluff until we get the essence. In other words, unlearning comes before learning. Systematic education, however, fills our heads with wrong mental models. One is the attitude that learning (in the broader sense of the word) is a necessary and sufficient condition for progress. Let us not forget that before we sow, we weed.

Unlearning and learning

Successful investing is directly proportional to our ability to be less stupid—to emphasize—not to be smarter but to do fewer stupid things.

How to achieve it? First, we eliminate the bad habits and then cultivate the good ones. Being less stupid is a consequence of our ability to eliminate the unnecessary. Yes, the ability to remove harmful programs is at least as important as the ability to install new ones. And every habit is a program.

Harmful habits are countless, while useful ones can be counted on two hands. We think that ROI (Return on Information) is directly proportional to the quantity of the information consumed. We like to frame and think binary. One of the most pernicious habits is the refusal to take responsibility for our actions.

What does it mean to break bad habits?

First, we must admit that we have such habits. Then, we must clearly describe them and proceed to the next step, which is to weed. There is no option for skipping steps. When we successfully remove a harmful habit, we should immediately replace it with a useful one. Let us not forget the rule of nature and vacuum.

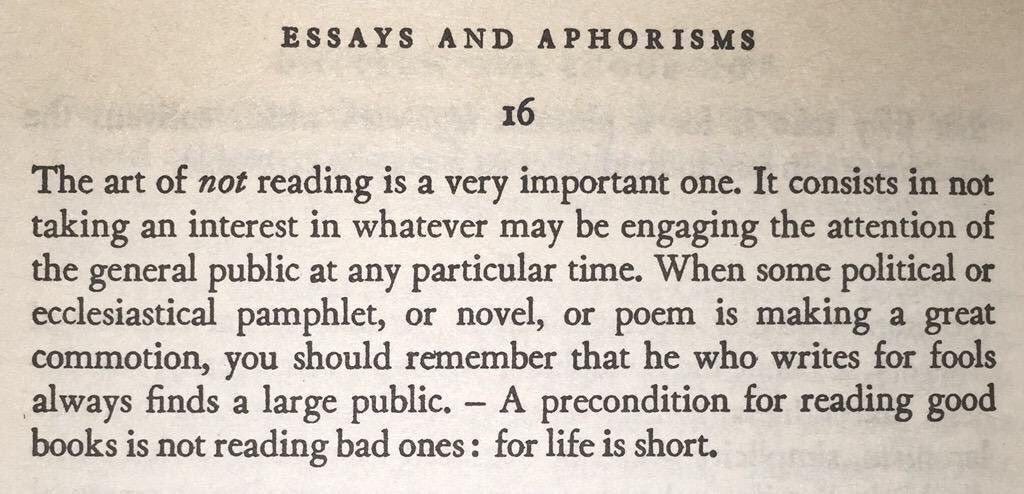

An example of the unlearning-learning process is the ability to select high-quality information sources. The first step is to stop consuming mainstream investment literature and media. The next is to choose new sources of information. Pareto's rule applies with full force—less than 20% of financial media and books deliver over 80% of the value.

If we haven't given up the bad habit of reading low-quality sources first, we won't have time for the quality ones. Let's not forget that there are 24 hours a day, and our attention can only focus on one place at a time. The two habits can't exist simultaneously; it's up to us which one we choose.

In this line of thought, I follow Arthur Schopenhauer's recommendation when selecting sources.

An essential prerequisite to consuming quality information is not to consume a bad one.

One of the must-have qualities of an investor is constantly asking questions about the world around us. In the next section, I look at the other qualities.

3+1 qualities for successful investors

Any challenging endeavor, such as investing, requires ambition in abundance. However, the level of achievement of our ambitions is a function of the pain we can endure. And we don't like to suffer.

We live in an age where comfort and security are the masters, and we are the servants. Too often, we prefer unhappiness to insecurity. Ultimately, we settle for a miserable but "secure" existence.

That's what we humans are - always looking for security, safety, and comfort. And all three of these, by definition, do not exist in markets but in life. In other words, there's a lot of pain to endure on the markets until we grasp how NOT to play the game.

To progress as investors, we must have a high pain threshold. However, enduring pain is not the only quality we need. What are the others?

In my opinion, every market player must cultivate:

Curiosity

Responsibility

Resilience

The willingness to ask questions about the world is a must. I don't know one successful person who doesn't read a lot. By successful, I do not mean multiple zeros on the bank account. Success is a function of the quality of the path these people have traveled to be who they are now. Curiosity about the world around us is one of the things they have in common.

And what to read, then?

Psychology, philosophy, history, statistics, economics, finance, and fewer books for traders and investors. At some point, the latter becomes more of a drag than a driver.

We've lit the spark with Dalio and Graham's books; it's time to grow the fire. To do this, we need specialized literature—statistics, economics, corporate finance, history, philosophy, and psychology—to extract the principles that great investors use.

The following quality, taking responsibility for our actions and their consequences, distinguishes a man from a boy. The inability to claim responsibility for our actions, especially failures, is inversely proportional to our chances of future success.

In financial markets, the feedback cycle is even shorter. I have a losing trade, not because the market is rigged, the Jews control the world, the Fed raised interest rates, or a black cat crossed my path, but because I made a decision based on which I took an action that in turn has a consequence.

And who made the original decision? Not some secretive Rothschild heir, Jerome Powell, or the cat. Only the person behind the keyboard was responsible for pressing the buy key.

The last quality I'll examine is perseverance. Slow but steady speed in the right direction will always beat high and erratic speed without direction. Investing is challenging and involves a lot of emotional pain, financial losses, and mental efforts. A lack of persistence will turn the cart around at our first shock.

The shocks are a must if we want to be successful in the markets. There is no option for stepping over, avoiding the pain. We have to move on, not despite the pain but because of it.

However, one last quality unites all three. It helps us when the emotional pain has once again reached its limit, we still blame the cat for our losing trade, and when we don't have the strength to read yet another report.

It is about the most underrated and hated quality in recent times—discipline. All three of the above attributes are cultivated with discipline. We may possess prodigious talent, but life brings countless examples of talented failures. On the other hand, discipline that leads to consistency defeats even the most outstanding but undisciplined talent in the long run. Discipline trumps talent and money and makes time work for us.

To be disciplined is to be your own worst tyrant. Nature does not tolerate a vacuum. If you are not, someone else will be.

Success and mediocrity do not belong in the same sentence. In other words, discipline is a must. Being disciplined will not guarantee success in the markets or life. Its absence, however, is the direct path to failure. We refuse to be disciplined at our peril.

Discipline and the ability to unlearn bad habits are the foundation of success. However, these are neither the end nor the beginning of our path. Our path begins with us and ends with us.

Know thyself

At the entrance to the Temple of Apollo in Delphi, it says the following:

Know thyself, nothing to excess; certainty brings insanity.

Knowing who we are, being moderate, and embracing uncertainty is the beginning. We declare that we are the only ones responsible for our existence. Knowing ourselves is the beginning and the end.

We only learn who we are when we unlearn who we are not. To be ourselves is to stop being who we are not. Again, the lesson of weeding and planting.

The basic tenet of all "gurus" is that the path to self is fun and easy. Mistake. If there is no resistance, there is no progress. If there is no progress, there is stagnation, and stagnation means death.

The path to self lies outside our tiny comfort zone, where we think everything is safe and guaranteed. If we find it difficult, then we have most likely stepped on our path. And if it's too easy, we're probably doing something wrong. We are stuck in our little circle of comfort.

Discipline tempers our perseverance, responsibility, and curiosity. With their help, we will continue on our path, not despite difficulties but because of them. To recap, fun is not out of the question as long as we can laugh at ourselves.

Humans are simultaneously simple and complex creatures. So is investing—a simple endeavor but not easy in practice. The reason is no secret. Physiology largely determines our reactions, thoughts, decisions, actions, and outcomes. However, our lack of discipline and refusal to take responsibility further amplifies the deficits of our hardware.

Whoever tells you that there is a short and easy path to success in the markets (and in life) wants something from you but does not offer anything in return except sugar-coated promises.

To take, we must first give. And it's not just about money but time and attention—let us not forget the phrase: pay attention. Of course, money is a necessary ingredient for investment, but it is only one of the three essential elements. Without enough time and effort to understand how much we do not understand, our money will quickly find its new owner.

Money and experience met. Money left with experience. The experience left with the money.

Unknown author

Then comes the stage of learning what NOT to do. If we haven't given up despite all the emotional and financial pain, the next step is learning what to do.

Well, then, there is no hope. No, there is. But it lies where we have a habit of not checking.

Great one! I was already fan of your analysis on seeking Alpha. Can't wait to get your calls here.