Uranium Part 2: Geography and Risks

Thoughts on Africa, Kazatomprom, and grey swans

Uranium is the most powerful energy source known to humankind…after stupidity. Anyway, today's topic is not our propensity for irrationality but one of the most asymmetric ideas: long yellow cake.

This is the second episode of Adventures in the Uranium Industry. In the previous one, I discussed the three mandatory ingredients for a plausible commodity thesis: stagnating supply, rising demand, and potential catalysts.

To recap why I believe a bull market in uranium is highly likely to stay:

Stagnant supply: lack of CAPEX for uranium projects; political and economic fragmentation; shortage of mining personnel.

Growing demand: AI and data centers, transition to clean energy, Global South demography, and geopolitical tensions.

Potential Catalysts: sanctions on Russian uranium imports/exports; large-scale accident in one of top five mines; supply chain disruptions; further supply cuts from Cameco and Kazatomprom

The demand growth rate exceeds the supply growth rate, and we have a few potential catalysts. Those facts make the uranium thesis relatively simple. However, this does not imply zero risk. The uranium idea comes with risks. In the last chapter, I will discuss the risk of uranium thesis in more detail.

Today’s topic is uranium geography, emphasizing the weak points in the supply chain. What does it mean weak points? The short answer is authoritarian countries as major suppliers. Therefore, supply cuts can occur at any time for multiple reasons.

Thoughts on uranium demand and supply

To gain context, we have to look at the major players on the uranium map. The following four charts show the distribution of uranium production between countries, mines, and companies.

Kazakhstan (43%), Canada (15%), and Namibia (11%) are the Big Three in uranium production. The following three countries are Australia, Uzbekistan, and Russia. Charts via Statista.

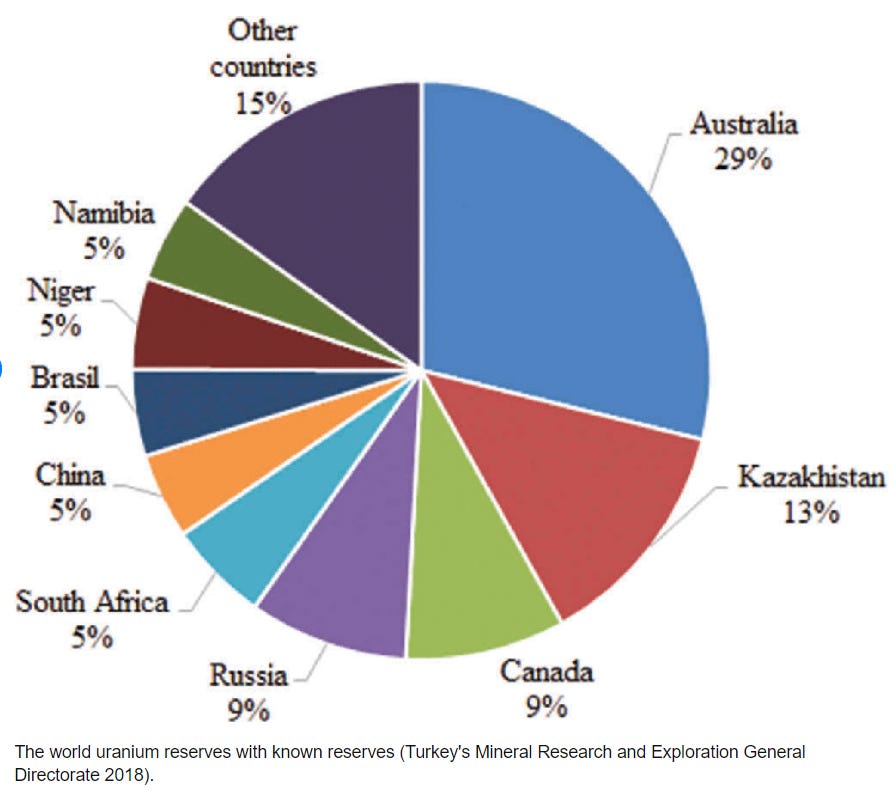

However, the distribution of reserves follows a different pattern: Australia, Kazakhstan, Canada, Russia, and Namibia.

To confuse things, the largest operating uranium mine is Cigar Lake in Canada, followed by Husab in Namibia and Inkai in Kazakhstan. Chart via WNA.

Cameco, Kazatomprom, Orano, and GCN (China General Nuclear) deliver more than 50% of the annual uranium production.

However, not all agents involved in the uranium market are equal. I find the authoritarian regimes and their allies the most interesting.

This observation automatically excludes Australia and Canada. As a side note, their governments became oppressive in multiple ways, disguised under the banner of liberalism. For today’s article, however, I will stick to the widely accepted standard for autocratic states. This means Russia, Kazakhstan, and the African states that are part of the Russo-Chinese sphere of influence.

Scramble for Africa 2.0

Until recently, France dominated Sub-Saharan Africa. However, French influence has been declining after a series of coups in the last four years. Neither nature nor geopolitics tolerate a vacuum. French influence is being replaced by Russian influence. What are all Great Powers looking for in the Sahel region?

The answer is resources. The Birimian Greenstone Belt is one of the world's largest gold deposits. It stretches over 2,000 kilometers longitudinally in the following countries: Burkina Faso, Niger, Ivory Coast, Mali, Ghana, and Guinea. In addition, there are deposits of several other minerals in the region:

One of the countries responsible for 20% of Europe's uranium supply is Niger. It ranks seventh in the world in annual production, and the SOMAIR mine produces 4% of annual uranium production. The mine is owned by the French company Orano, one of the most prominent uranium mining and processing players. The following graph shows the uranium import sources for Europe:

On July 28, 2023, another coup took place in the region - the military took over the capital of Niger, Niamey. Niger was the last country in the region to have civilian rule. Following coups in recent years, all its neighbors are ruled by military juntas.

The new regime in Niger is pro-Russian, and on the third day after the coup, its leader announced that he was suspending uranium and gold exports to France. Russia has concessions to develop uranium mines in numerous countries. The same applies to platinum, gold, and diamonds.

Russian interest in Africa is backed by its military. The image below shows Russia's military presence in Africa:

Many of the poorest countries, but with abundant resources, have defense agreements with Russia.

The African continent is the new theatre where the geopolitical chess between the Great Powers unfolds. The exploitation of raw materials is only part of the motivation. Among the tools of economic warfare is cutting enemies’ access to resources. This is precisely what is happening in Africa right now, and the coup in Niger illustrates this principle in action.

Uranium has become a geopolitics lever, and Russia is best positioned to use it. Let’s not forget Russia’s role in the uranium/nuclear fuel production cycle:

Conversion: 37% of all uranium is processed in Russia

Enrichment: 44% of all uranium is enriched in Russia

Bonus: Russia mines over 10% of the world's uranium

Besides Russia, China is heavily involved in Africa. China is the second largest consumer of uranium after the US and imports from Kazakhstan, Namibia, and Russia. The Dragon is also actively buying stakes in companies developing fields in Africa. Their focus is on Namibia, which ranks fifth in the world in uranium reserves and second in annual production.

Through state-owned enterprises China General Nuclear (GCN) and China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), China controls some of the country's most attractive deposits:

Langer Heinrich - the mine has not operated since 2017 due to low uranium prices. In 1Q24, the mine started production again. Langer is owned by Paladin Energy Ltd (75%) and CNNC (25%).

Rossing is an open-pit mine that produces 5% of the world's uranium. CNNC owns and operates the mine.

Husab is an open-pit mine that produces 7% of the world's uranium. GCN owns and operates the mine.

China's uranium glut is not a coincidence. It is building 21 new nuclear reactors. Faced with a growing uranium deficit, the Chinese are doing what they are best at—planning for decades, in that case, stocking as much uranium as possible. China plans to build up reserves sufficient to power its reactors for ten years.

The discussion of uranium would be incomplete without the largest landlocked country, Kazakhstan, which shares borders with Russia and China. Kazakhstan dominates the uranium landscape with the highest annual output, second-largest reserves, and lowest AISC. However, that might change, considering recent developments.

Kazakhstan and Kazatomprom

The last few weeks have brought important news, indicating shifts in Kazakhstan's uranium supply. Higher taxes, rising AISC, and declining output signal further uranium deficit. Kazatom's 1H25 figures are telling:

Cash cost +38%,

AISC +45%,

CAPEX +64%,

Corporate income tax +81%

Mineral Extraction Tax (MET) +104%

In addition, Kazatom announced its 2025 Production Guidance. The expected output is -13.65 million lbs or a 17% YoY decline. That's nearly 10% of the global uranium supply.

To make things more exciting, on 10 July, Kazatom announced increases to Kazakhstan's Mineral Extraction Taxes (MET). A recently introduced 6% MET for 2024 will rise by 50% to 9% in 2025, then double again to as high as 18%.

Higher taxes and production costs will push KAP JV partners to reconsider their presence in Kazakhstan. Potential issues with the Caspian Route add more uncertainty to the equation. Eventually, mining in Canada and Australia may become more attractive for Kazatom JV partners.

Another overlooked aspect is to whom Kazatom delivers its uranium. In the 1H24 report, the company reveals that 47% of group production was sold to China. Moreover, Kazakhstan's government gave Rosatom the rights to 100% of JV Budenovskoye's output from 2024 to 2026. The outcome is less uranium for the West.

The supply distribution slowly shifts in Russia/China's favor. EU and the US urgently have to develop their uranium mines or establish new supply lines to ensure energy sovereignty. However, there are two obstacles: building a mine takes years, and over 70% of the global uranium supply comes from countries under Russo-Chinese influence.

In conclusion, the uranium thesis remains intact. Yet, I am not saying it is bulletproof. Yellow cake play carries a few considerable risks. The prime ones are not rooted in market dynamics but elsewhere. In the following paragraphs, I discuss grey swans, uranium alternatives, and false flag operations.

Risks

Uranium thesis risks fall into a few categories:

Black Swan events or the unknown unknown

Grey Swan events or the known unknown: Fukushima 2.0; Ukraine-Russia war as a catalyst

Demand specific: thorium as uranium alternative

Supply specific: sudden increase in supply from Kazakhstan

The Black Swan events are characterized by unpredictable timing, unknown probability, and uncertain consequences. That’s why I call them unknown unknowns.

Grey Swan events are known unknowns. In that case, we can define the potential catalyst and its consequences with adequate credibility. What we don't know is the timing and probability distribution. Uranium thesis known unknowns are:

A large-scale NPP accident not caused by war. I refer to the Fukushima and Chornobyl disasters.

A large-scale NPP accident caused by war. The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP) and Kurchatov Nuclear Power Plant (KNPP) have central roles in Russian and Ukrainian strategic planning.

ZNPP is Europe's largest nuclear power plant. This fact makes ZNPP a negotiation tool with more weight than the KNPP. Nonetheless, both NPPs may serve as a trump card for the belligerents.

An example is Ukraine forces launching missiles containing spent nuclear fuel at the ZNPP reactors. Then, Ukraine may claim that Russia shelled the reactors to create a “false flag” situation that would trigger NATO intervention. Russia also can use KNPP for similar provocation only to justify the use of tactical nuclear weapons later during the war. Those alternatives have multidimensional consequences not limited to the local theatre of war. They may signal that we have passed a point of no return, i.e., the conflict spirals into NATO vs. Russia direct military engagement.

As stated, those risks fall in the Grey Swan category. The odds and timing are impossible to measure. If a “false flag” operation affecting one of the NPPs comes into play, the nuclear energy dawn will turn into the sunset, resulting in plummeting uranium prices.

Market-specific risks have a low potential to undermine my idea (at least for now). Thorium does not carry significant risk for the uranium thesis because it will take years, even decades, to widely adopt it as a uranium replacement. A supply glut caused by Kazakhstan’s production boost is unlikely, considering the last Kazatom reports. In summary, the market risks, i.e., thorium adoption and supply flood, fall in the “possible” category, which is far from “probable.”

Final thoughts

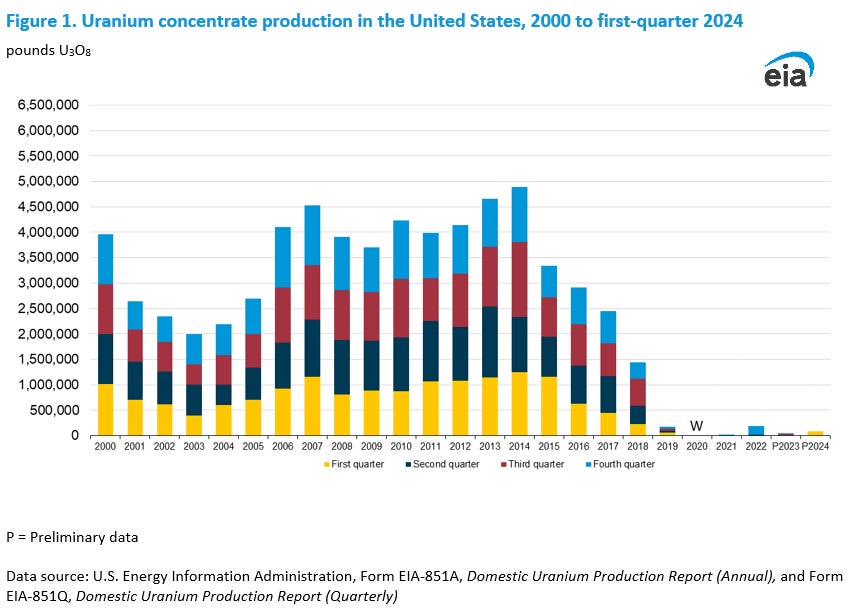

The United States is the largest consumer of uranium in the world. They consume as much as the second (China) and third (France) combined. At the same time, uranium production in the US has hit new record lows. The graph from EIA shows the dismal quarterly results.

The chart implies that the US depends heavily on imports. The following countries are major suppliers:

Kazakhstan 35%

Canada 15%

Australia 14 %

Russia 14 %

5 % own production

49% of uranium imports come from Russia and Kazakhstan. For reference, the US chiefly relied on domestic uranium supply during Cold War 1.0. The graph below from EIA shows US uranium sources from 1950-2020.

The divergence between domestic production and imports peaked in the last ten years. Depending on an adversary or, let's say, neutral state actors to source critical materials for national defense and energy sovereignty is not geopolitically wise. It brings short-term gains but then comes with a steep price.

US dependency on imports from non-friendly countries illustrates that the uranium thesis is based not only on structural deficit but also on supply redistribution. In other words, the latter amplifies the former.

Like all critical minerals, uranium is a tool to exert geopolitical power. China and Russia hold strong hands in that game, while the EU and the US bear weak cards. The big winners, however, are uranium investors. If no grey swan events occur, the uranium bull has a long time to run.

This was the second chapter describing my adventures in the uranium universe. In the last one, I will share some ideas on how to bet on uranium.

Everything described in this report has been created for educational purposes only. It does not constitute advice, recommendation, or counsel for investing in securities.

The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the author and are subject to change without notice. You are advised to do your own research and discuss your investments with financial advisers to understand whether any investment suits your needs and goals.

In order to use the uranium 238 you mine you have to enrich it by increasing the uranium 235 concentration.

Enrichment is essential.

Sylex technology is very interesting.

Cameco invested in it and sylex is listed in Australia.

Recommend to review the enrichment and smelting issues in uranium mining. procedures.

Interesting recap and look foward to third chapter

Great piece mate - Wish I had discovered your Substack earlier. Uranium thesis fundamentals more bullish than ever, market sentiment hates it more than ever 😂