The Banco de Avío, established in Mexico in 1830, was the country’s first development bank and a pioneering institution in LatAm. Founded by Lucas Alamán after independence, its mission was to provide low-interest loans to entrepreneurs, primarily to modernize the textile industry.

Over twelve years, it financed machinery purchases and industrial growth, contributing about one million pesos in loans, mainly to the cotton sector. Although the bank was dissolved in 1842, it remains a core part of LatAm economic history, introducing new technologies and laying the foundation for Mexico’s banking industry.

Yes, we are heading again to Mexico for the second chapter of my adventures. This is the April Beyond Equity report for TheOldEconomy Pro subscribers. It covers Mexican banks as fixed-income plays. As usual, the report starts with the essence: inflation and rates.

Rating, inflation, and yield curve

First, the basics: Mexico’s credit rating and its position compared to the rest of the world. Credit ratings are essential indicators of a country’s creditworthiness, directly impacting borrowing costs, investor confidence, and access to international capital. Look at the map below:

The world’s highest-rated countries, such as Switzerland, Germany, and Australia, hold AAA ratings, reflecting minimal default risk and strong fiscal management. Most advanced economies cluster in the AA to A range, while emerging markets and developing nations span BBB to B or lower, with higher risk premiums and more volatile access to financing.

Mexico currently holds an investment-grade rating of BBB (S&P scale). This rating places Mexico near the bottom of the investment-grade spectrum, on par with countries like India and Greece, but several notches below top-rated peers. The ratings reflect Mexico’s adequate economic policies and diversified economy.

A robust credit rating of Mexican government bonds also implies lower risk for corporate issues. In the past 12 months, Mexican corporate bond issuances have reflected growing demand for EM HY instruments. Mexican companies are among the most significant corporate bond issuers.

Mexico’s active bond market underscores investor confidence and the country’s fiscal credibility. Obviously, Mexican bonds attract capital. Then what about their yield? To answer that question, we need to start with the inflation expectations.

In the first quarter of 2025, Mexico’s inflation showed a modest upward trend but remained comfortably within the central bank’s target range of 2% to 4%. Annual inflation reached 3.80% in March, the highest level this year, but still below the 4% upper threshold set by the Bank of Mexico.

The rise in March was driven primarily by higher prices for food, alcohol, and tobacco, which increased by 4.15% year-on-year. Housing inflation eased slightly to 3.64%, while core inflation, which excludes volatile items like food and energy, remained stable at 3.64% in March. The central bank responded to the contained inflation by cutting its benchmark interest rate by 50 basis points to 9% in March, signaling the potential for further easing if inflation continues to moderate.

The above paragraphs are summarized in the image below (via JP Morgan):

Unlike Brazil or Colombia, Mexican interest rates correlate highly with US rates. The relationship is too apparent to ignore, reflecting the two countries' deep economic and financial ties. The following illustrates that:

Mexico’s sensitivity to FED rates is the highest in LatAm and nearly double that of the regional average. Historically, when the Fed raises its benchmark rate, the Mexican Central bank often follows suit, sometimes almost automatically, to prevent capital flight, support the peso, and contain imported inflation. In 2025, as FED rates remained steady, the Mexican central bank began cutting its rates from a peak of 11.25% to 9%, responding to easing inflation and weak economic growth.

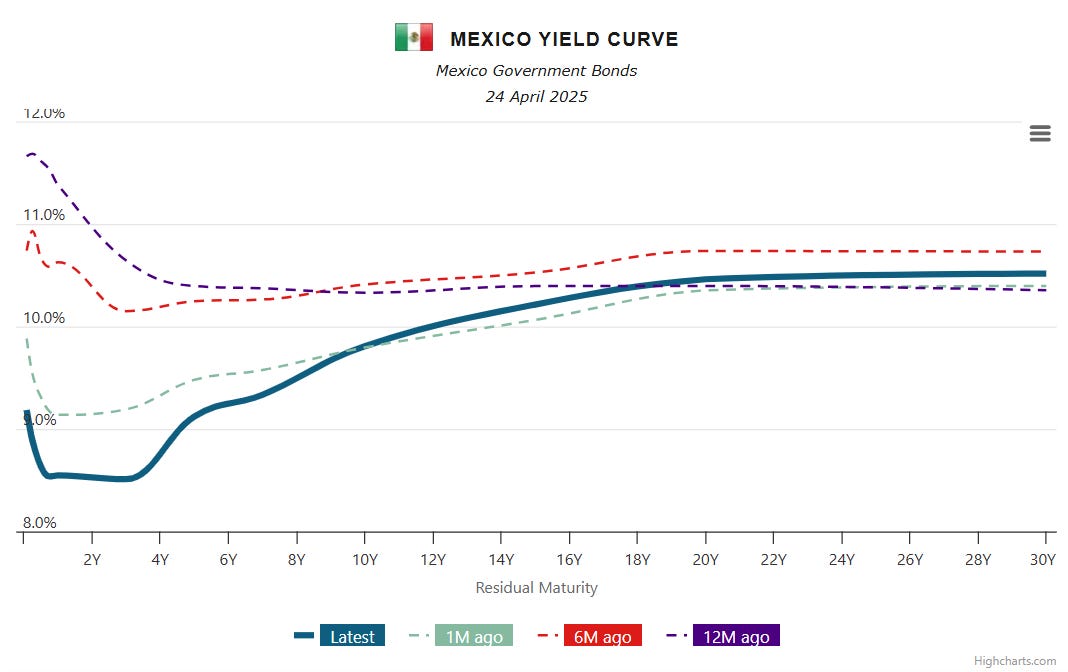

During 1Q25, Mexico’s yield curve reflected both domestic monetary policy easing and heightened global uncertainty. Nevertheless, the YC is in a steepening regime, i.e., the spread between long-term and short-term bonds is expanding.

The March rate cut led to a noticeable decline in short-term yields, with Cetes (short-term government securities) adjusting quickly to the new policy. However, the long end of the yield curve remained elevated, with the 10-year government bond yield hovering around 9.6% and forecasted to close the quarter near 9.5%.

Overall, the Mexican yield curve in 1Q25 exhibited a flattening trend at the short end, reflecting monetary policy cuts, but stayed relatively steep at the long end due to persistent risk factors and uncertainty, limiting the potential for a broader decline in yields.

Steepening YC, attractive real rates, and stable-ish inflation make Mexican corporate bonds, especially long-end, lucrative. The bank industry is one of my favorite places to seek HY ideas. Mexican banks, unsurprisingly, have a lot to offer.

A side note: This is the third report covering corporate bonds issued by banks. Last time, I asked How to Lend Money to Swiss Bankers, while in February, I looked for HY picks in Brazil.

Now, back to business.