Does the quality of the investment process guarantee profitable trades?

We are fully responsible for the former; however, we have no control over the latter. That said, we frequently have high-conviction positions, played according to our plan, that do not deliver the expected results.

Out of ten trades, we may have five or even more losing positions. So, we know the frequency of winners and losers with high confidence. What we do not know is their distribution. We may have five consecutive losses or five consecutive winners. Accordingly, to get the chance to score the five winning trades, we expose ourselves to the risk of going through five losing trades as well.

Since we are betting on the future, and the future is, by definition, unknowable, there is always a chance we could be wrong, no matter how brilliant our investment process is. The purpose of our process is, first and foremost, to ensure our survival, i.e., avoiding significant irreversible losses.

To survive, we need a structured investment process that leads to well-argued and precisely executed positions. Our trades fall into two prime categories: quality trades (this does not mean that they are consistently profitable): "Well played, losing trades," and "Well played, winning trades."

Our job as market participants is to never fall into the category of "Poorly played trades, no matter the outcome." Even if we win several times in a row, the lack of an investment process will cost us dearly.

The following quote by Annie Duke eloquently sums it up:

“Thinking in bets starts with recognizing that there are exactly two things that determine how our lives turn out: the quality of our decisions and luck. Learning to recognize the difference between the two is what thinking in bets is all about.”

Annie Duke

The quality of the investment process is not proportional to its complexity. Overcomplication does not lead to better decisions, just as too much information does not increase the quality of the hypotheses we generate.

Few but sufficient moving parts make a mechanism efficient. So, too, with the investment process – pick only the core variables and cut the unnecessary fluff. Thus, our process significantly improves, and the number of wrong decisions with irreversible outcomes sharply decreases.

In other words, by aiming for simplification, we avoid the ego trap of proving ourselves to be the smartest and the fallacy that complexity leads to certainty.

Investing does not reward the brightest minds. Counterintuitively, market success is directly proportional to our ability to be less stupid, not the smartest. Accordingly, seeking certainty in a place where the only assurance is uncertainty and change is absurd. Let’s not forget the financial markets are synonymous with change and uncertainty.

What does a sufficiently simplified investment process mean?

It must answer a few deceptively simple questions:

· Where to invest?

· Why invest?

· How much does it cost?

· When to buy/sell?

· How much to buy/sell?

Most market participants focus on the first question: Where to invest? A smaller proportion also asks Why? and How much? However, the last two questions are as ignored as they are misunderstood.

As a side note, investing psychology is even more ignored than risk management. How we think about markets and life predetermines how we play them, hence the outcomes. If you enjoy philosophy reads, I have two article series for philosophers investors (Links: Part 1 and Part 2).

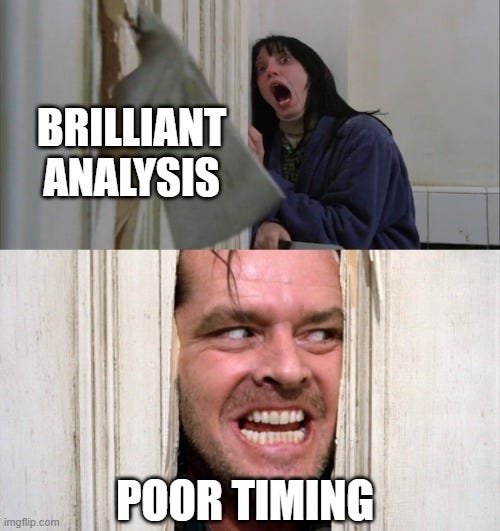

“When” and “How much” describe risk management as the last but most important stage in our investment process. Timing and position sizing carry more weight than the analysis quality in our long-term performance.

In the long run, an analyst who is a good enough risk manager beats a brilliant analyst but a mediocre risk manager.

Risk management has two objectives: first, to ensure our survival, and second, to ensure our chance to make profits. Even impeccable risk management does not guarantee profits; it only skews the odds in our favor.

When we invest, we are betting not only on the occurrence of event X but also on its timing. Timing considers when we expect event X to happen, i.e., when the price of the asset will move in the desired direction, hence when it is a good time to buy. To emphasize, timing does not equal the "perfect" time to buy, but at least the inappropriate one.

The number of positions we take depends on the probability of being right and the risk-reward ratio. Ideas that are highly asymmetric in our favor and have a high degree of credibility deserve more capital than ideas with lower asymmetry and/or lower degrees of credibility. Again, both extremes are dangerous—taking too much risk and taking too little risk.

Investing is simple but not easy. It requires us to think in probabilities in the context of time. Neither are habitual for humans because our thought process is optimized for linear thinking.

At the same time, we tend to complicate things by adding more linearity while trying to solve non-linear puzzles such as financial markets. By appending more complexity, we pump our egos about how clever we are and fool ourselves into thinking that the more complex our process is, the more plausible the outcome is. Two mistakes that cost us dearly.

Then, what to do?

Simplify. This means quantitative and qualitative change, i.e., removing what is superfluous. We need an investment process that is sufficiently simplified to ensure, above all, our survival so that we can get a chance to generate profits. Never forget that profits are optional.

Our trades fall into two categories: "Well Played, Losing Trades" and "Well Played, Winning Trades." A lack of process results in "Poorly played trades, no matter the outcome."

The essential variables that turn a trade into “Well Played” are timing and quantity, i.e., when and how much to buy. Our long-term performance in the markets lies in the answers to these two questions: risk management.

We ignore risk management at our own peril. If we don't manage risk, it will manage us.

PS: talking about timing, analysis, and risk management.